On October 8, 2024, an eight-year-old girl in Kampala, Uganda, arrived at the Vine Medicare Clinic with a headache, fatigue and a vivid rash covering her arms, chest, back and legs. Her symptoms indicated mpox—a highly contagious viral infection that was recently declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization—so frontline workers quickly transferred her to an isolation room for treatment, allowing them to safely manage her symptoms while preventing further spread of the disease. Meanwhile, another health care worker sounded the alarm to district colleagues through a dedicated reporting hotline, triggering outbreak investigation efforts that ultimately allowed the team to mount a response—while the patient made a full recovery.

The health facility that sounded the alarm is partnering with Uganda’s Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), Ministry of Health (MOH) and Resolve to Save Lives through an initiative called Epidemic-Ready Primary Health Care, or ERPHC, which prepares primary care providers to prevent epidemics, including by training and mentoring health care workers on how to detect and report suspected disease cases. This continues to be a major bottleneck for epidemic prevention, and it’s one of the primary focus areas of ERPHC. Without timely alerts, outbreaks can spread unchecked, overwhelming health systems and costing lives. Through ERPHC, health facility staff are primed to sound the alarm and make sure every outbreak is stopped in its tracks.

What is Epidemic-Ready Primary Health Care?

An Epidemic-Ready Primary Health Care (ERPHC) system is one that can prevent, detect, and respond to outbreaks while maintaining essential health services. An ERPHC system can find cases quickly, manage them safely and cope with the increased demands they bring. Through our ERPHC initiative, we’re partnering with primary health care facilities to ensure they are “epidemic-ready”—by strengthening relationships between facilities and the communities they serve and by training and mentoring health care workers to prevent, detect, and manage outbreaks while protecting themselves and others.

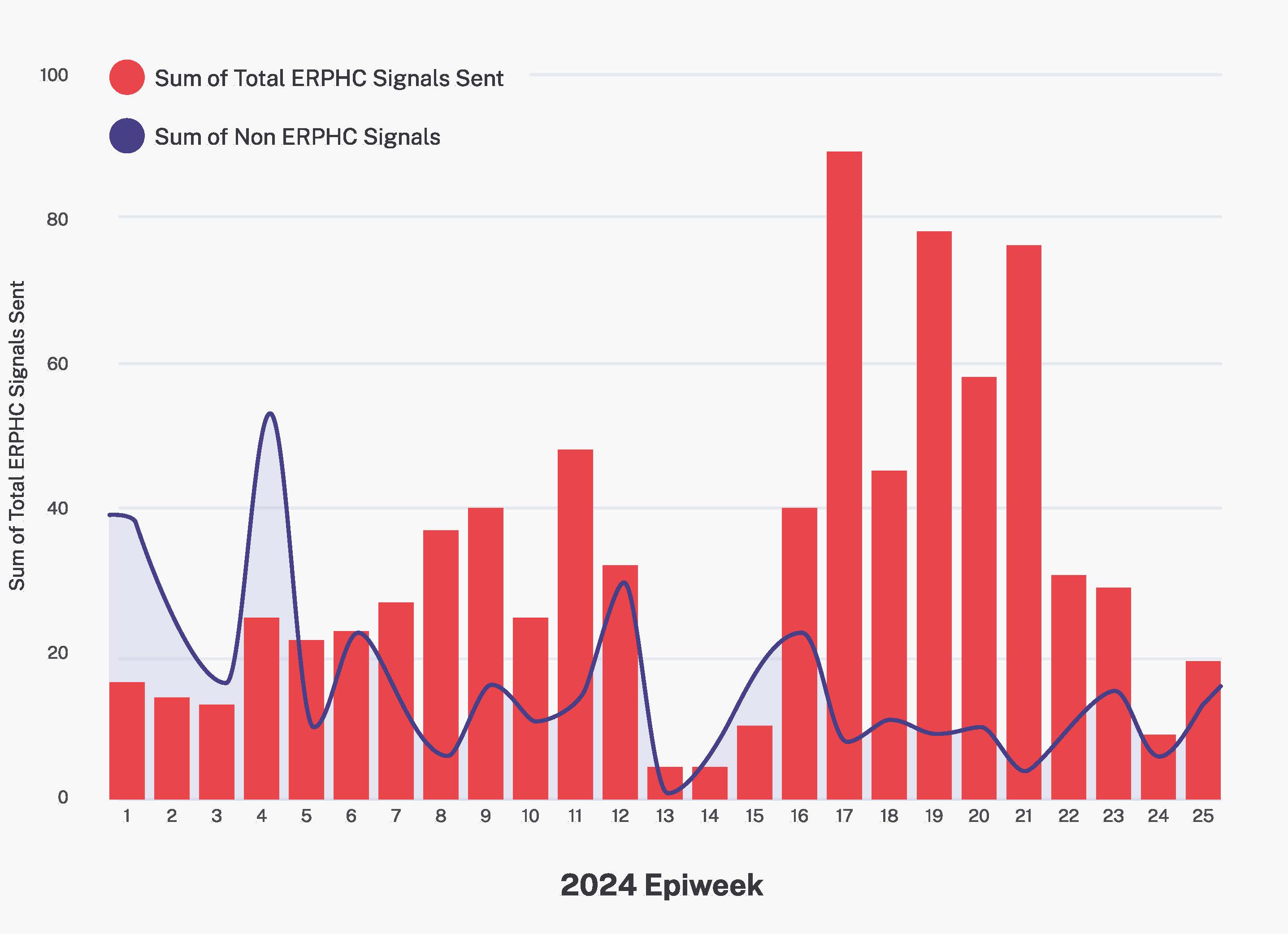

“Through our partnership with IDI and MoH, we’re providing training and mentorship to frontline workers at 330 public and private primary health facilities across 19 districts,” said Leena Patel, a Senior Advisor for Epidemic Intelligence at Resolve to Save Lives. “Even after just a few months, we’re already seeing a huge increase in the number and quality of alerts—including more alerts for priority diseases and fewer false alarms.”

The power of mentorship

Abdullah Wailagala at Uganda’s Infectious Diseases Institute has been spearheading this effort at IDI. “When we assessed health care worker knowledge and understanding before implementing ERPHC, many could not correctly identify when and how to create an alert, and many didn’t know how to correctly use our reporting hotline, 6767. In a very short time, we’ve seen remarkable improvements in progress, as evidenced by the increase in alerts seen on various reporting platforms and progress recorded on our standardized mentorship tool.”

“Even after just a few months, we’re already seeing a huge increase in the number and quality of alerts—including more alerts for priority diseases and fewer false alarms.”— Leena Patel, Resolve to Save Lives

The mentors are all Ugandan health care workers from neighboring health facilities, and they provide guidance to their mentees on how to identify and report cases through extended training sessions, monthly mentorship visits and ongoing logistical support. The mentorship tool was developed by Resolve to Save Lives to facilitate productive conversations between mentors and mentees, allowing them to identify and discuss both strengths and areas for improvement, including infection prevention and control behaviors and surveillance best practices. The tool emphasizes active listening, building trust and encouragement as core mentoring skills to support fruitful ongoing relationships that ultimately translate to improved practices and better management of public health threats at ERPHC facilities.

During monthly visits, mentors support the health facilities with forecasting for the month ahead, in addition to assessing the facility’s overall performance and reviewing findings for ongoing areas of improvement. Each ERPHC region has a priority pathogen schedule that is reviewed on a monthly basis, which helps to prime health facilities to detect and respond to specific pathogens. This schedule is based on predictable seasonal surges in disease, such as increases in cases of anthrax and cholera that can follow annual heavy rainfall, as well as sporadic outbreaks like the recent surge in mpox across the region.

A surge in quality alerts

The platforms for reporting suspected disease cases have witnessed a surge in alerts since the health facilities started implementing ERPHC. “Across Uganda, ERPHC districts are dominating the alerts landscape,” said Patel, adding that this success is likely due to the mentoring provided to ERPHC facilities. “Before this partnership, the 19 districts were creating fewer alerts compared to non-ERPHC districts across the country. But after implementing ERPHC, these 19 districts are now creating 57% of the nation’s alerts—despite making up just 14% of the nation’s districts.”

Godfrey Bongole at Uganda’s Infectious Diseases Institute led efforts to analyze data from Uganda’s national DHIS2 database to understand the impact of ERPHC by comparing ERPHC districts with those that did not receive the interventions. “We compared ERPHC and non-ERPHC districts both before and after implementation of ERPHC, to make sure the increase in both number and quality alerts can be attributed to the training and mentoring,” he said, adding that “both the number and quality of alerts is clearly better in ERPHC districts after implementation.”

“…both the number and quality of alerts is clearly better in ERPHC districts after implementation.” — Godfrey Bongole, Uganda Infectious Diseases Institute

As Bongole notes, the increase in alerts is a rise in quantity and quality. 44% of alerts from ERPHC districts were created for “priority” diseases of importance to Ugandan health authorities, versus 40% from non-ERPHC districts. What’s more, only 2% of alerts were deemed “unactionable” versus 5% in non-ERPHC districts, and only 36% were deemed “unnecessary for public health action” versus 41% in non-ERPHC districts. Essentially, this means that ERPHC districts are producing fewer false alarms, thereby minimizing wasted efforts in the quest to prevent epidemics.

A challenge with the results is that data is aggregated at the district, rather than health facility, level, so it cannot quantify the exact contributions of ERPHC facilities. It’s possible that mentors working with ERPHC facilities may return to their own facilities and implement new practices there, thereby amplifying the number of facilities using these approaches. However, the team is confident that there have been no other interventions during this time that could explain the surge in alerts from ERPHC districts. In addition, the “priority” diseases that are the focus of ERPHC account for nearly 80% of the alerts in the supported districts, suggesting the increase is driven by ERPHC facilities.

Expanding the ERPHC program

Next, the team will continue its partnership with the 330 health facilities, and explore ways to capture the impact at the health facility, rather than district, level, to understand possible “spillover effects” to non-ERPHC facilities. They will also look at expanding the program to other types of health facilities, as well as introducing the program to other districts across Uganda. Ultimately, the team hopes the findings from implementing ERPHC in Uganda will also serve as an exemplar to other countries in the region seeking to overcome the longstanding bottleneck of alerts delaying effective responses to outbreaks.

“Our partnership with IDI and MoH demonstrates that investing in health care workers really works,” said Patel. “By providing timely alerts, health care workers are helping to stop outbreaks before they start and, in doing so, providing an invaluable service to their patients and communities.”

Find out more about Epidemic-Ready Primary Health Care (ERPHC) here.