How we save lives / Blood pressure control / Frequently Asked Questions: Hypertension Management

HYPERTENSION FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Updated January 2024

You’ve been redirected. LINKScommunity.org is now part of resolvetosavelives.org.

Resolve to Save Lives gathered the following questions from trainees and health care providers in the countries where we work.

They are grouped into six thematic sections, listed below. A Glossary of terms and acronyms can be found following the final section.

Sections

HYPERTENSION TREATMENT PROTOCOLS, CARE PROCESS, COST CONSIDERATIONS

- Alignment with current treatment guidelines or clinical practice

- Cost of drugs and ease of procurement

- Simplicity

- Evidence that certain drug classes may be less effective or have more side effects in the population to be treated*

* For example, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are unsafe in women who are of child bearing potential and are contraindicated in pregnancy. There is evidence that ACE inhibitors are less effective and have more angioedema in black American populations as compared to Caucasian populations.2 For the most part, however, the differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs in other ethnic populations has not been studied.

References

- Jaffe MG, Frieden TR, Campbell NRC, et al. Recommended treatment protocols to improve management of hypertension globally: A statement by Resolve to Save Lives and the World Hypertension League (WHL). The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2018;20(5):829-836. doi:10.1111/jch.13280.

- The Allhat Officers and Coordinators for The Allhat Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in Moderately Hypercholesterolemic, Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Pravastatin vs Usual Care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(23):2998-3007. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2998.

Answer: WHO, RTSL and their partners advocate for two hypertension treatment protocols.1 One starts treatment with a fixed-dose dual drug combination (preferably both medicines combined into a single pill), while the other starts with single medications (“monotherapy”). Both recommend using combinations of two or more medicines, as separate pills as needed, if blood pressure remains uncontrolled after the initial treatment. Both WHO protocols recommend the same three core medication classes (calcium channel blockers, renin-angiotensin system blockers, and thiazide diuretics). Ultimately, each jurisdiction should adapt the WHO protocol templates to align with local clinical guidelines, prescribing practices, drug availability and pricing, and other contextual factors within a country or health system.1 In the Global Hearts initiative, because of the advantages of long-acting calcium channel blockers listed above, almost all countries have adopted simple treatment protocols, including amlodipine, for initial treatment (alone or in combination).

Generally, recommendations prioritize medications that are long-acting, affordable, possess a reliable supply, and have demonstrated success in clinical trials.2

- Al-Makki A, DiPette D, Whelton PK, Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Acharya S, Beheiry HM, Champagne B, Connell K, Cooney MT, Ezeigwe N, Gaziano TA, Gidio A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Khan UI, Kumarapeli V, Moran AE, Silwimba MM, Rayner B, Sukonthasan A, Yu J, Saraffzadegan N, Reddy KS, Khan T. Hypertension Pharmacological Treatment in Adults: A World Health Organization Guideline Executive Summary. Hypertension. 2022 Jan;79(1):293-301. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18192. Epub 2021 Nov 15. PMID: 34775787; PMCID: PMC8654104.

- Tran, D. N. et al. Ensuring Patient-Centered Access to Cardiovascular Disease Medicines in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries Through Health-System Strengthening. Clin. 35, 125–134 (2017). Hamdidouche, I. et al. Drug adherence in hypertension: from methodological issues to cardiovascular outcomes. J. Hypertens. 35, 1133–1144 (2017).

References

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-Guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2.

- Tran DN, Njuguna B, Mercer T, et al. Ensuring Patient-Centered Access to Cardiovascular Disease Medicines in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries Through Health-System Strengthening.Cardiology Clinics. 2017;35(1):125-134. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2016.08.008.

- Multi-country Regional Pooled Procurement of Medicines. Identifying key principles for enabling regional pooled procurement and a framework for inter-regional collaboration in the African, Caribbean and Pacific Island Countries. WHO/TCM/MPM/2007.

- The Allhat Officers and Coordinators for The Allhat Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in Moderately Hypercholesterolemic, Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Pravastatin vs Usual Care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(23):2998-3007. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2998.

Answer: Although there is evidence that adding a second drug is five times more effective than intensifying dosage of the first drug,1, 2 adding a second drug can increase barriers to access and may not be appropriate in all settings. Dose intensification using the same medication (e.g. intensifying from one pill to two) can limit some of these barriers: the patient may have to make fewer trips to the pharmacy, and may pay less, than if a second drug were added. There may also be reduced dispensing burden to the pharmacy, thereby enhancing treatment escalation efficiency.3 The need for lab tests is different across calcium channel blockers (CCBs), ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or thiazide diuretics. For example, intensifying a CCB is likely to require fewer lab tests, which may be preferable in settings in which access to lab tests is limited.4 In the future, if fixed-dose combinations of anti-hypertensive medications are available in appropriate dosages, intensification with multiple drugs may be simpler for patients, health care providers, and pharmacies, and these problems would not arise.

For patients with highly elevated blood pressures, it is important to note that dosage titration and sequential addition of other agents will be required to achieve blood pressure control.3

References

- Markovitz AA, Mack JA, Nallamothu BK, Ayanian JZ, Ryan AM. Incremental effects of antihypertensive drugs: instrumental variable analysis.Bmj. 2017. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5542.

- Law MR. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials.Bmj. 2003;326(7404):1427. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1427.3.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- HEARTS Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: evidence-based treatment protocols. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/NMH/NVI/18.2). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

References

- Santschi V, Chiolero A, Colosimo AL, et al. Improving Blood Pressure Control Through Pharmacist Interventions: A Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3(2). doi:10.1161/jaha.113.000718.

- Proia KK, Thota AB, Njie G, et al. Economics of Team-based Care in Controlling Blood Pressure. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;47( ):86-99. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.00.

- Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community Health Workers in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries: An Overview Their History, Recent Evolution, and Current Effectiveness. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014;35(1):399-421. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182354.

- Abegunde D. Can non-physician health-care workers assess and manage cardiovascular risk in primary care? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85(6):432-440. doi:10.2471/blt.06.032177.

Answer: Although some clinical guideline developers from professional societies and at the World Health Organization have emphasized hypertension treatment decisions based on predicted 10-year cardiovascular disease risk, risk-based approaches have not been evaluated rigorously, and implementation may not be feasible in many settings.

An alternative to the risk-based approach posits that large numbers of low- and moderate-risk hypertensive patients can be treated efficiently and effectively when treatment is simple and highly-standardized.1 This approach includes focusing on a very small core of generic and inexpensive but safe and effective medications that can be made readily available in bulk to organized treatment programs. It also emphasizes developing straightforward protocols for treatment that, in initial stages, can be executed by health care workers with relatively limited oversight from costly physician/specialist groups. Long-term follow up care can also be delivered in this context. Similar models have shown that by treating large numbers of patients in this manner, within 10 to 15 years the pool of hypertensive patients advancing to high-risk status can dramatically decline, resulting in reduced rates of severe cardiovascular disease and stroke. 2, 3 Furthermore, by implementing standard treatment programs for all patients with elevated blood pressure, many systems will be able to treat more high-risk patients than they would be trying to find and separately treat these individuals.

There is evidence indicating the limitations of risk-based approach (in which predicted risk is based on not only blood pressure, but also age, sex, and presence or absence of other risk factors.) In many clinical settings, risk assessments are not performed even when recommended.1 If treatment thresholds are based on risk assessment, treatment is not likely to be prescribed when the risk assessment has not been done or is unknown. Furthermore, some people with hypertension (~10%) have low short-term cardiovascular risk; with a risk threshold approach, they would may not receive treatment, which may lead to long-term health consequences. 4

A further limitation of the risk-based approach is that resources are directed to a relatively small proportion of all hypertensive patients, who often require physician/specialist care, laboratory resources, and other costly measures. Focus is directed away from the large numbers of low- or moderate-risk hypertensive patients, e.g., individuals who may be in lower risk categories with systolic blood pressure between 140 and 160 mmHg. Because 10-year risk predictions are strongly influenced by the patient’s current age, the risk-based approach most often doesn’t select younger adults for treatment, even though most of the adverse health consequences of uncontrolled hypertension are cumulative over time. Under the risk-based protocols, lower 10-year risk patients are followed with lifestyle recommendations. However, this may be inappropriate, as almost all international guidelines recommend treating all patients with persistent hypertension above 140/90 mmHg with medication, and in resource-poor environments, these patients will often be lost to follow up before they are ever treated. Inevitably, as high-risk patients are treated, their ranks will be refilled by current low- or moderate- risk patients who will become high-risk over time, so that the overall numbers of deaths prevented are not dramatically reduced. Nonetheless, in some settings with severe resource constraints, risk-based approaches may be used to rationally allocate scarce resources.

A separate role of cardiovascular risk assessment is to identify patients, particularly those who have had a prior cardiovascular event, who will benefit from more intensive care, potentially including statins, aspirin, and beta blockers, among other measures. This is a highly effective means of reducing individual risk, although the impact on population-wide health may be limited.

References

- Angell SY, Cock KMD, Frieden TR. A public health approach to global management of hypertension. The Lancet. 2015;385(9970):825-827. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62256-x.

- Jaffe MG, Young JD. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Story: Improving Hypertension Control From 44% to 90% in 13 Years (2000 to 2013). The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2016;18(4):260-261. doi:10.1111/jch.12803

- Ikeda N, Sapienza D, Guerrero R, et al. Control of hypertension with medication: a comparative analysis of national surveys in 20 countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;92(1). doi:10.2471/blt.13.121954.

- Campbell NR, Khan NA, Grover SA. Barriers and remaining questions on assessment of absolute cardiovascular risk as a starting point for interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24(9):1683-1685. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000242387.92225.c8.

Answer: “Doctor, I usually take my high blood pressure medicine every day—but not today!” This patient story is familiar to health care workers who manage blood pressure all over the world. The only solution to the missed medication dose scenario is to instruct the patient to take their medications and repeat the blood pressure measurement while on the medication, for example one week later. Health care workers should not guess what the treated blood pressure would be, as individual patients respond differently to antihypertensive medications.

Repeat visits to physicians due to missed medication doses may not be feasible in busy practices. In such situations, asking non-physician health care workers to perform the repeat blood pressure measurement (task-sharing) may be a more efficient and viable solution.

Answer: Hypertension treatment protocols often do differ for patients with severely raised blood pressure. Risk for cardiovascular events associated with raised blood pressure increases as blood pressure increases; more severe hypertension (e.g. ≥180 mmHg systolic blood pressure or ≥110 mmHg diastolic blood pressure) represents a higher risk state than do lower hypertension-range blood pressures. In addition, certain sequelae of hypertension (hemorrhagic stroke, hypertensive retinopathy, acute kidney failure) are more likely to occur at severely elevated blood pressures.

Resolve to Save Lives hypertension treatment protocols recommend starting treatment the same day for blood pressure ≥160/100 mmHg. Some, but not all protocols recommend starting with a higher initial antihypertensive medication dose or multiple medications for blood pressure ≥160/100 mmHg (e.g. amlodipine 10 mg versus amlodipine 5 mg; or one full pill of telmisartan 40 mg in combination with amlodipine 5 mg).

People who have symptoms of new or worsening target organ damage related to increased blood pressure (e.g. crescendo angina, confusion, acute kidney failure etc.) represent a medical emergency and need rapid care.1

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

Answer: For asymptomatic patients, Resolve to Save Lives treatment protocols recommend discontinuing one medication (usually the last medication prescribed) if systolic blood pressure is below 110 mmHg.

Systolic blood pressures below 90 mmHg should trigger stopping of all antihypertensive drugs until blood pressure is re-assessed (ideally within the next seven days) if the patient is asymptomatic.

Patients with low blood pressures should return for repeat blood pressure measurement and be evaluated for factors that may lead to transient lower blood pressures, including side effects from other medications, dehydration, acute inflammatory conditions, or measurement error.

Significant symptomatic reductions in blood pressure require immediate individualized assessment and management.

References

- Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Fernández JR. Decreasing Sleep-Time Blood Pressure Determined by Ambulatory Monitoring Reduces Cardiovascular Risk.Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58(11):1165-1173. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.043.

- Rahman M, Greene T, Phillips RA, et al. A Trial of 2 Strategies to Reduce Nocturnal Blood Pressure in Blacks with Chronic Kidney Disease.Hypertension. 2013;61(1):82-88. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.112.200477.

BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

Answer: When used correctly, automated, digital blood pressure measurement devices are highly reliable and preferable to manual blood pressure devices.1 Blood pressure is rarely measured using recommended technique in clinical practice. Automated devices have several distinct advantages that reduce user error and facilitate accurate blood pressure readings: they simplify the measurement process; eliminate errors related to hearing deficits, parallax, incorrect initial inflation pressure and rapid deflation; enable multiple measurements to be taken sequentially; and allow unobserved measurements to be performed (reducing white-coat effect). In theory, automated blood pressure measurement also eliminates terminal digit preference (rounding of the last digit that is commonly done by observers using the auscultatory method,) but only if the exact blood pressure result displayed on the device is used for clinical decision-making.

Multiple international protocols and standards have been developed to test the accuracy of automated devices, including a recently published unified international standard.2 One important accuracy requirement is that the devices produce blood pressure measurements that are within 5±8 mmHg of an auscultatory reference standard (which is meticulously performed, standardized, simultaneous, blinded two-observer auscultation performed using a sphygmomanometer known to be accurate.) It is important to use an automated device that has passed one of these standards, preferably the new unified one, in a study performed by an independent authority (i.e., not by the manufacturer themselves or an organization affiliated with the manufacturer).

References

- Padwal R, Campbell NRC, Schutte AE, et al. Optimizing Observer Performance of Clinic Blood Pressure Measurement: A Position Statement from the Lancet Commission on Hypertension Group. J Hypertension In press.

- Stergiou GS, Alpert B, Mike S, et al. A Universal Standard for the Validation of Blood Pressure Measuring Devices. Hypertension. 2018;71(3):368-374. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10237.

- If the first blood pressure (BP) is <140/90 mmHg, then no other blood pressure measurement is needed during that encounter. Use the first (and only) BP as the recorded BP.

- There is a 95% chance that second BP will be lower than the first, so if the first BP is <140/90 mmHg, the mean blood pressure would be <140/90 mmHg.2

- If the first BP is >140/90 mmHg, perform a second BP and use the second reading as the recorded BP for the encounter.

- Averaging the two measurements to determine mean BP in a busy primary care setting is a time-consuming exercise and is potentially prone to errors.

- Using the second BP measurement without averaging will result in a slightly lower recorded BP compared to mean BP, but will still result in a recording that is over goal when both readings are >140/90 mmHg.

- When the first reading is >140/90 mmHg and the second reading is <140/90 mmHg, using the second BP measurement without averaging is preferable and will result in a slightly lower recorded BP compared to mean BP.

- Despite resulting in some blood pressures that are recorded as <140/90 mmHg when the mean BP being slightly over 140/90 mmHg, the second, lower measurement is likely closer to the actual average than the first, because the first BP measurement in a series is usually the highest and most abnormal. Subsequent repeated measurements have a tendency to be less abnormal, related to the observed phenomenon described as “regression to the mean.”

- If there is a large difference between the first and second reading (>5 mmHg), it is reasonable to do a third measurement and use the third BP as the recorded BP.

- A third BP is often much closer to the second BP than to the first BP, moving the mean closer to the second and third BP measurements.

- Using the second BP measurement (or third, if done) as the representative BP may misclassify a small number of individuals who have a mean BP slightly above 140/90 mmHg to a recorded BP slightly under 140/90 mmHg. However, this is preferable to the potential errors associated with manual averaging at a large scale.

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Handler J, Zhao Y, Egan BM. Impact of the Number of Blood Pressure Measurements on Blood Pressure Classification in US Adults: NHANES 1999-2008. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2012;14(11):751-759. doi:10.1111/jch.12009.

Answer: Terminal digit bias is the tendency of an observer to round up, or down, a measurement to a digit of his or her own choosing, usually to zero. For example, an observer has the tendency to record a BP reading of 144/97 mmHg as 140/100 mmHg.

Observer bias occurs when the observer has a preconceived idea of what the blood pressure ought to be, leading to an arbitrary adjustment of the reading. It usually occurs when an arbitrary threshold is applied between normal and high BP, for example 140/90 mm Hg. An observer might tend to record a more favorable (under the threshold) measurement in a young healthy man with a borderline increase in BP and a less favorable one (above the threshold) in an obese, middle aged man with a similar reading. Likewise, there might be observer bias in over-reading BP to facilitate recruitment in a hypertension registry, or under-reading if there is a need to ration medications due to a shortage of medications. Intended or not, both of these types of biases can lead to inaccurate BP recordings, even among observers who have performed many BP measurements.

Why are terminal digit bias and observer bias important clinically?

Terminal digit bias and observer bias can lead to errors in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension by systematic under- or over-estimation of the patient’s blood pressure. Because hypertension is diagnosed and treated based on blood pressure thresholds (140 mmHg systolic and 90 mmHg diastolic), terminal digit bias and observer bias can result in under- or over-diagnosis as well as under- or over-treatment of hypertension. One study found that terminal digit preference was generally associated with artificially lower recorded blood pressures and lower likelihood of being prescribed the antihypertensive medication that is indicated.1 Delayed treatment or undertreatment of elevated blood pressure puts patients at higher risk of cardiovascular disease events. Over-diagnosis and over-treatment of hypertension results in unnecessary medication side effect risks and costs. Another study showed that terminal digit preference was associated with overdiagnosis, where raising the threshold for hypertension from >140 to >141 would reduce the diagnosis of hypertension from 25.9% to 13.3% in that clinical dataset.2

How can terminal digit bias and observer bias be addressed and corrected?

Evidence shows that monitoring with regular feedback of data and training can reduce terminal digit and observer bias.3,4

Below are 3 steps to identify and reduce these biases across facilities and healthcare workers.

Step 1: Identify and Monitor

- Review paper or electronic blood pressure records and observe staff measuring patients’ blood pressure.

- Look for two signs of bias (see the Figure below):

- Rounding – Proportion of systolic and diastolic readings ending in “0”. The expected proportion ending in “0” should be approximately 10%.

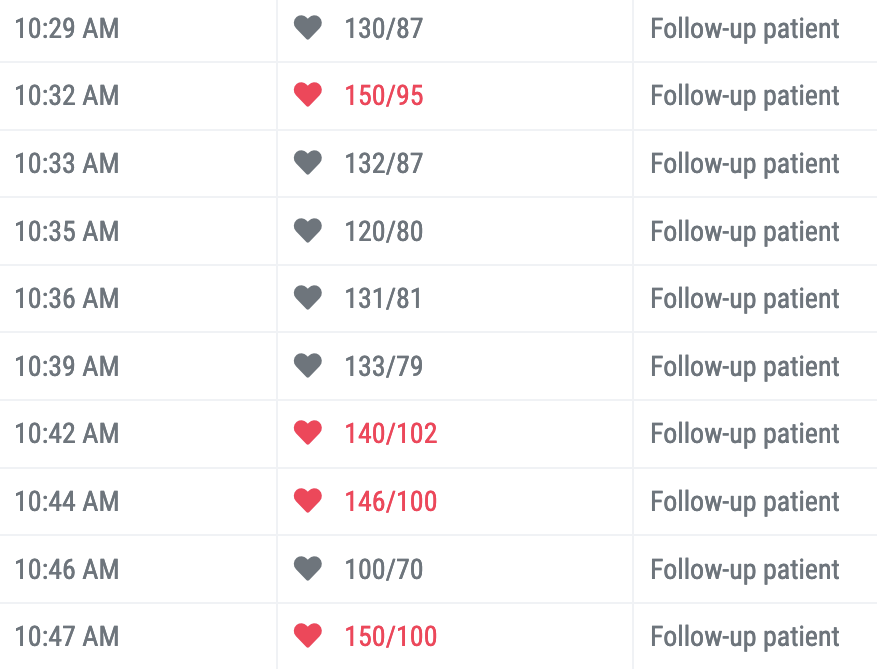

- Gaming – High number of readings that are just above or below threshold of 140/90, e.g. 138/88, 139/89, 140/90, 141/91Figure: example of terminal digit bias In the blood pressure data from a single clinical facility, six of ten (60%) systolic blood pressure readings and four of the ten (40%) diastolic readings below are rounded to “0”. Can you find them? Without terminal digit preference bias, the expected proportion of all numbers that terminate with a zero should be about 10%.

Step 2: Provide feedback and training

- Provide ongoing feedback for sites that continue to have bias. Many healthcare workers may not be aware of terminal digit and observer bias.

- Ask them not to round.

- Explain how rounding and observer bias can cause errors in diagnosis and treatment, leading to adverse clinical outcomes for patients

- During training sessions, advise staff to record the exact blood pressure that is measured without rounding.

Step 3: Encourage use of automatic over manual BP devices when available

- Digital blood pressure measurement devices show the precise blood pressure numbers and discourage biased readings. Studies have demonstrated that using automated blood pressure devices reduces terminal digit bias.5,6 Whenever validated electronic devices are available, their use should be promoted. Keep in mind that most facilities that employ digital devices still require observers to manually enter the blood pressure numbers on a paper form or computer—there is still room for error and bias!

References

- Nietert PJ, Wessell AM, Feifer C, Ornstein SM. Effect of terminal digit preference on blood pressure measure- ment and treatment in primary care. Am J Hypertens 2006; 19(2): 147–152. PMID: 16448884

- Wen SW, Kramer MS, Hoey J, Hanley JA, Usher RH. Terminal digit preference, random error, and bias in routine clinical measurement of blood pressure. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46(10): 1187–1193. PMID: 8410103.

- Boonyasai R, Carson KA, Marsteller JA, et al. A bundled quality improvement program to standard- ize clinical blood pressure measurement in primary care. J Clin Hypertens 2018;20:324–33. PMID: 29267994<

- Wingfield D, Cooke J, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Fletcher AE, Fagard R et al. Terminal digit preference and single- number preference in the Syst-Eur trial: influence of quality control. Blood Press Monit 2002; 7(3): 169–177. PMID: 12131074

- Greiver M, Kalia S, Voruganti T, et al. Trends in end digit preference for blood pressure and associations with cardiovascular outcomes in Canadian and UK primary care: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024970. PMID: 30679298

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ 2011;342:d286. PMID: 21300709

Answer: Opportunistic screening for hypertension is recommended, by conducting measurement of blood pressure (BP) for all adults visiting primary health care facilities. A commitment to comprehensive opportunistic screening means having sufficient capacity in terms of health workers trained in measurement and BP measurement devices. To estimate the number of BP devices required per facility, it is important to know three data points: 1) average daily number of adult patient visits at the facility, 2) average duration of time to screen one patient [e.g. 2 minutes], and 3) number of hours the facility is open per day.

The average daily number of total adult patient visits can generally be estimated by reviewing facility registers. This count should assume that a BP monitor can be positioned centrally in the facility where the maximum number of adults can be screened. This location could be at the same location as the facility entryway, registration desk or triage station. Particular patient groups, such as pediatric patients or adult trauma patients could be excluded from the count.

The duration of time to screen one patient can be determined by direct observation in a facility by timing the length of time it takes for a health care worker to screen a patient, measure their BP, and document any record-keeping, before moving on to the next patient. Since at many facilities, the staff who screen blood pressures also have additional tasks (e.g. documenting registers), the time per screening can be variable across hypertension programs. Therefore, it may be necessary to directly observe and measure the time per patient for opportunistic BP screening. This length of time (e.g. 2 minutes) can then be used to determine how many patients can be screened by that health care worker (and BP device) per hour (e.g. 2 minutes per patient = 30 patients screened per device per hour). Facilities can modify the number of BP devices and health care workers that need to be assigned for opportunistic BP screening at a facility by reducing the time it takes to screen each patient through decreasing documentation time and off-loading other tasks from BP screening stations.

The number of hours the facility is open per day can be quantified by telephone survey or in-person observation.

With the above 3 data points, the following formula can be used to estimate the number BP of devices for opportunistic screening at a facility:

| Numerator: | Average number # of adults seen at facility per day |

| Denominator: | [(Number # of patients screened/device/hour ) x (Number # of hours facility open per day] |

| Example: | If a facility:

250/(30×4)= 2 devices (and 2 health care workers) needed for opportunistic BP screening at that facility * Please note that this calculation is a guide. Each facility needs to assess how this result practically fits with their facility staffing model and workflows. For example, if the calculation above shows a need for 5 devices but the facility will only have 1 or 2 BP screening stations (and 1-2 staff taking measurements), then 5 devices may be too many. |

Answer: White coat hypertension (WCH), also known as white coat syndrome, refers to elevated blood pressure readings observed during clinic visits despite evidence of consistently normal-range blood pressure values outside of the medical setting.1

WCH is thought to be triggered by anxiety or stress related to the medical environment, causing a temporary rise in blood pressure that does not reflect the patient’s typical daily levels.1 When WCH is suspected, it can be diagnosed by measuring out-of-office blood pressure. Out-of-office- blood pressure can be assessed as the average of one week’s worth of daily seated home blood pressure measurements or using the 24-hour mean blood pressure from 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.2

The European Society of Hypertension considers individuals with an office blood pressure mean of at least 140/90 mmHg and a mean 24-hour blood pressure of less than 130/80 mmHg to have WCH.3 The 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines recommended systematically lower threshold values to define hypertension.4 Accordingly, the guidelines define WCH as a clinic blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg or above, accompanied by 24-hour blood pressure or home blood pressure readings below 130/80 mmHg. 4

- Nuredini, G., Saunders, A., Rajkumar, C. & Okorie, M. Current status of white coat hypertension: where are we? Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 14, 1753944720931637 (2020).

- Staessen, J. A. et al. Task Force II: Blood pressure measurement and cardiovascular outcome. Blood Press. Monit. 6, 355 (2001).

- O’Brien, E. et al. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J. Hypertens. 31, 1731–1768 (2013).

- Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertens. Dallas Tex 1979 71, e13–e115 (2018).

Answer: Untreated white coat hypertension (WCH) has been estimated to have a borderline 36% higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with consistent normotension, but cardiovascular risk is much higher with sustained hypertension (100%, or two-fold higher CVD risk compared with normotension).1,2 WCH patients have a three- to fourfold higher risk of developing sustained hypertension within 10 years compared with patients with consistent normotension. because of this, we recommend more frequent follow-up and out–of–office blood pressure assessments (where possible), and a lower threshold to initiate medication treatment in people with suspected WCH. If WCH is suspected and medication treatment is continued, treated patients should be followed up to ensure no adverse medication effects such as lightheadedness or risk of falls.

Clinical decisions regarding antihypertensive treatment and target goals rely on empirical evidence. To identify cases of WCH, hypertension diagnosis should ideally be based on documented elevated 24-hour blood pressure monitoring or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) where technically and logistically feasible, . Out-of-office blood pressure measurement is a particular priority for patients with high absolute cardiovascular risk and evidence of hypertensive target organ damage.3

- Cohen JB, Lotito MJ, Trivedi UK, Denker MG, Cohen DL, Townsend RR. Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in White Coat Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jun 18;170(12):853-862. doi: 10.7326/M19-0223. Epub 2019 Jun 11. PMID: 31181575; PMCID: PMC6736754.

- Shimbo D, Muntner P. Should Out-of-Office Monitoring Be Performed for Detecting White Coat Hypertension? Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jun 18;170(12):890-892. doi: 10.7326/M19-1134. Epub 2019 Jun 11. PMID: 31181573.

- Staessen, J. A. et al. Task Force II: Blood pressure measurement and cardiovascular outcome. Blood Press. Monit. 6, 355 (2001).

- Aburto, N. J., Ziolkovska, A., Hooper, L., Elliott, P., Cappuccio, F. P., & Meerpohl, J. J. (2013). Effect of lower sodium intake on health: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ, 346, f1326. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f1326

- He, F. J., Li, J., & Macgregor, G. A. (2013). Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 346, f1325. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f1325

DIET AND LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS TO LOWER BLOOD PRESSURE

Answer: The term ‘borderline’ is not a good way to describe hypertension, which is one of the world’s leading risks for death. If a person’s usual blood pressure is >140/90 mmHg, * they are considered to have hypertension according to most clinical guidelines and are likely to benefit from antihypertensive drug treatment.

Clinical trials indicate that more rapid blood pressure control is associated with fewer cardiovascular disease events, and in most people, this can only be achieved with antihypertensive drug treatment. Although it is important to advise lifestyle changes to people with hypertension, very few people are able to change their lifestyles extensively enough to control hypertension.

Some trials that delivered standardized diet interventions under controlled conditions (i.e., food consumed by participants was prepared by study staff, as in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) trial) achieved systolic blood pressure reductions of >10 mmHg, which is comparable to the blood pressure-lowering effect of a single standard dose antihypertensive medication.2,3 However, trials of lifestyle change advice delivered in real-world primary care settings, in which participants prepare their own food, have demonstrated a more modest reduction in blood pressure (about 2 mmHg systolic), and it is unclear if this effect can be sustained for more than one or two years.4 Hence drug treatment should not be delayed while waiting for lifestyle change effects on blood pressure.

Lifestyle change remains an important complement to medication. Evidence shows that adherence to a low sodium diet can potentiate the blood pressure- lowering effects of particular antihypertensive medications (e.g., diuretics and renin-angiotensin system blockers).5,6

* >130/80 mmHg if they have diabetes or chronic kidney disease, according to some authorities1

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A Clinical Trial of the Effects of Dietary Patterns on Blood Pressure. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336(16):1117-1124. doi:10.1056/nejm199704173361601.

- Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on Blood Pressure of Reduced Dietary Sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(1):3-10. doi:10.1056/nejm200101043440101.

- O’Connor EA, Evans CV, Rushkin MC, Redmond N, Lin JS. Behavioral Counseling to Promote a Healthy Diet and Physical Activity for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Adults With Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020 Nov 24;324(20):2076-2094. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17108. PMID: 33231669.

- Slagman MCJ, Waanders F, Hemmelder MH, et al. Moderate dietary sodium restriction added to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition compared with dual blockade in lowering proteinuria and blood pressure: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2011;343(jul26 2):d4366-d4366. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4366.

- Ram CV, Garrett BN, Kaplan NM Moderate sodium restriction and various diuretics in the treatment of hypertension. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1981;141(8):1015-1019. doi:10.1001/archinte.141.8.1015.

Answer: Resolve to Save Lives treatment protocols provide guidance at sequentially increasing doses and numbers of drugs to control hypertension and prevent cardiovascular death and disability. Drug titration should be undertaken regardless of the ability of the person to follow lifestyle change advice.

Although lifestyle changes can be effective at lowering blood pressure and can potentiate the blood pressure-lowering effects of specific antihypertensive medications,1 very few people are able to make the changes necessary to control blood pressure. Unhealthy built and nutritional environments (which are appropriate targets for population-wide public health approaches) are common and make lifestyle change very challenging.

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

Answer: Blood pressure starts to rise as alcohol consumption exceeds two standard drinks a day.1* (Because women have lower levels of an important enzyme that metabolizes alcohol and on average are smaller than men, many recommendations suggest that women not exceed one standard drink per day.)2 Patients who have a history of alcoholism or who have liver disease should not consume any amount of alcohol, and consuming no alcohol in a day is considered healthy for everyone.

The pattern of alcohol consumption may be more important than the cumulative yearly average consumption. A binge-drinking pattern has been associated more strongly with risk for cardiovascular disease death.3 People with hypertension are at elevated cardiovascular disease risk and should avoid binge drinking.

*One standard drink includes: 12 ounces of regular beer, which is usually about 5% alcohol, or 5 ounces of wine, which is typically about 12% alcohol, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits, which is about 40% alcohol. Source: U.S. National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism

References

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Tobe SW, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Rehm J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(2). doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30003-8.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Britton A. The relation between alcohol and cardiovascular disease in Eastern Europe: explaining the paradox. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2000;54(5):328-332. doi:10.1136/jech.54.5.328.

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE MEDICATIONS: SELECTION OF DRUG CLASS

References

- Jaffe, M. G. et al. Recommended treatment protocols to improve management of hypertension globally: A statement by Resolve to Save Lives and the World Hypertension League (WHL). J. Clin. Hypertens. 20, 829–836 (2018).

- The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in Moderately Hypercholesterolemic, Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Pravastatin vs Usual CareThe Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA 288, 2998–3007 (2002).

- Al-Makki A, DiPette D, Whelton PK, Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Acharya S, Beheiry HM, Champagne B, Connell K, Cooney MT, Ezeigwe N, Gaziano TA, Gidio A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Khan UI, Kumarapeli V, Moran AE, Silwimba MM, Rayner B, Sukonthasan A, Yu J, Saraffzadegan N, Reddy KS, Khan T. Hypertension Pharmacological Treatment in Adults: A World Health Organization Guideline Executive Summary. Hypertension. 2022 Jan;79(1):293-301. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18192. Epub 2021 Nov 15. PMID: 34775787; PMCID: PMC8654104.

- in Guideline for the pharmacological treatment of hypertension in adults [Internet] (World Health Organization, 2021).

- Under Pressure. (n.d.). Resolve to Save Lives. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from https://resolvetosavelives.org/cardiovascular-health/hypertension/under-pressure/

- Tran, D. N. et al. Ensuring Patient-Centered Access to Cardiovascular Disease Medicines in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries Through Health-System Strengthening. Clin. 35, 125–134 (2017). Hamdidouche, I. et al. Drug adherence in hypertension: from methodological issues to cardiovascular outcomes. J. Hypertens. 35, 1133–1144 (2017).

Answer: Most national guideline formulation committees consider angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) therapy equally effective in controlling hypertension and reducing hypertension-related adverse cardiovascular outcomes.1,2 High quality head-to-head outcome trials comparing ACE inhibitors to ARBs are limited, leading to conflicting evidence on the equivalence of ACE inhibitors and ARBs.3,4,5 The decision to use either ACE inhibitors or ARBs is usually determined by availability, affordability, and tolerability.

There is a broad consensus that the combination of two renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (typically ACE inhibitor and ARB) should not be prescribed.1, 2,6

At present, ARBs are usually more expensive than ACE inhibitors. However, as all the major medications are off patent, it may be possible to reduce medication costs for ARBs in the future.

Many clinicians have expressed a strong preference for medications that minimize adverse events. An important distinction between ACE inhibitor and ARB is the relative frequency of the cough adverse effect – which occurs in approximately 10% of people with ACE inhibitor and < 1% with ARB.7, 8 Approximately 3% of patients discontinue ACE inhibitors due to the known side effect of cough.5 Angioedema, a potentially life-threating allergic reaction, has been reported among those on ACE inhibitors (<1%), and, to a lesser degree, those taking ARBs.9, 10

There is also some evidence that specific populations may have fewer side effects with ARBs than with ACE inhibitors. One study indicated that individuals of recent African descent have a higher incidence of angioedema while taking ACE inhibitors.11 According to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension Guidelines, ARBs may be better tolerated than ACE inhibitors in black patients, with less cough and angioedema. However, based on the limited available evidence, ARBS offer no proven advantage over ACE inhibitors in preventing stroke or cardiovascular disease in this population, making thiazide diuretics or CCBs the best initial choice for single-drug therapy in this population.5

References

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management.2011.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-Guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2.

- ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events.J ournal of Vascular Surgery. 2008;48(2):499. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.06.009.

- Bangalore S, Fakheri R, Toklu B, Ogedegbe G, Weintraub H, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in Patients Without Heart Failure? Insights From 254,301 Patients From Randomized Trials.Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2016;91(1):51-60. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.019.

- Brugts JJ, Vark LV, Akkerhuis M, et al. Impact of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on mortality and major cardiovascular endpoints in hypertension: A number-needed-to-treat analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2015;181:425-429. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.179.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Overlack A. ACE Inhibitor Induced Cough and Bronchospasm. Drug Safety. 1996;15(1):72-78. doi:10.2165/00002018-199615010-00006.

- Bangalore S, Kumar S, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Associated Cough: Deceptive Information from the Physicians Desk Reference. The American Journal of Medicine. 2010;123(11):1016-1030. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.06.014.

- Toh S, Reichman ME, Houstoun M, et al. Comparative Risk for Angioedema Associated With the Use of Drugs That Target the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(20):1582. doi:10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.34.

- Makani H, Messerli FH, Romero J, et al. Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials of Angioedema as an Adverse Event of Renin–Angiotensin System Inhibitors. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2012;110(3):383-391. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.034.

- Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J, et al. Incidence and Characteristics of Angioedema Associated With Enalapril. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(14):1637. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.14.1637.

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management.2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-Guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Iskedjian M, Einarson TR, Mackeigan LD, et al. Relationship between daily dose frequency and adherence to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Clinical Therapeutics. 2002;24(2):302-316. doi:10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85026-3.

- Flack JM, Nasser SA. Benefits of once-daily therapies in the treatment of hypertension. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2011:777. doi:10.2147/vhrm.s17207.

Answer: Yes. The most recent US hypertension guidelines list CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and thiazide diuretics equally as first-line antihypertensive agents.1

The ALLHAT study compared the effects of an ACE inhibitor (lisinopril), a CCB (amlodipine), and a thiazide-like diuretic (chlorthalidone) on the incidence of fatal CHD or non-fatal myocardial infarction among those with hypertension and at least one other CHD risk factor. There were no significant differences among groups in the rate of the primary outcome, nor in all-cause mortality. The trial found those randomized to the chlorthalidone had lower systolic blood pressure at five years and a lower rate of heart failure as compared to those randomized to the ACE inhibitor or CCB; those randomized to the thiazide diuretic also had lower incidence of total CVD and stroke. The authors of the study therefore recommended thiazide diuretics as a first-line agent, except when not tolerated, and that thiazide diuretics be included in multi-drug regimens to treat hypertension.2

References

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- The Allhat Officers And Coordinators For The Allhat Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in Moderately Hypercholesterolemic, Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Pravastatin vs Usual Care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(23):2998-3007. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2998.

Answer: The evidence base supporting a thiazide diuretic/ACE inhibitor combination is strong. The ALLHAT trial showed thiazide diuretics to be generally equivalent to CCBs in monotherapy (with the exception of heart failure prevention for which thiazide diuretics were superior.)1 The thiazide diuretic/ACE inhibitor single pill combination was used successfully in a large hypertension management program in North America that achieved a 90% hypertension control rate. 2, 3 Although the ACCOMPLISH trial found that a CCB/ACE inhibitor combination was superior to a thiazide diuretic/ACE inhibitor combination,4 some authors have commented that the dose of the thiazide used, hydrochlorothiazide, was lower than the 25 to 50 mg dose of hydrochlorothiazide (similar to 12.5 to 25 mg of chlorthalidone) used in thiazide trials demonstrating the favorable outcomes.1, 5, 6

There are many reasons that the ACE inhibitor/thiazide diuretic combination remains particularly compelling. Fixed-dose combination medications (single pill combination) have been shown to increase adherence and simplicity for both doctors and patients.7 – 9 Also, the joint physiologic actions of the two components can synergistically reduce adverse event risks: thiazide diuretics counteract the risk of hyperkalemia due to ACE inhibitor and ACE inhibitor reduce the risk of hypokalemia due to thiazide diuretics. There are many fixed dose combination thiazide diuretic/ACE inhibitor products that are produced by generic manufacturers. The most important factors to consider are local/regional drug availability and affordability. If available and affordable, selecting specific drug combinations that have been used in successful clinical trials is reasonable.

References

- The Allhat Officers and Coordinators for The Allhat Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in Moderately Hypercholesterolemic, Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Pravastatin vs Usual Care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(23):2998-3007. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2998.

- Handler J. Commentary in Support of a Highly Effective Hypertension Treatment Algorithm. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2013;15(12):874-877. doi:10.1111/jch.12182.

- Jaffe MG, Young JD. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Story: Improving Hypertension Control From 44% to 90% in 13 Years (2000 to 2013). The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2016;18(4):260-261. doi:10.1111/jch.12803.

- Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus Amlodipine or Hydrochlorothiazide for Hypertension in High-Risk Patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(23):2417-2428. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0806182.

- Turnbull F. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. The Lancet. 2003;362(9395):1527-1535. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14739-

- Cutler JA, Davis BR. Thiazide-Type Diuretics and β-Adrenergic Blockers as First-Line Drug Treatments for Hypertension. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2691-2705. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.107.709931.

- Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, Messerli FH. Fixed-Dose Combinations Improve Medication Compliance: A Meta-Analysis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(8):713-719. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.033.

- Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, Safety, and Effectiveness of Fixed-Dose Combinations of Antihypertensive Agents. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):399-407. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.109.139816.

- Weeda ER, Coleman CI, Mchorney CA, Crivera C, Schein JR, Sobieraj DM. Impact of once- or twice-daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic cardiovascular disease medications: A meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;216:104-109. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.082.

Answer: Technically, no. Most guideline development groups do not distinguish amongst specific agents in the thiazide/thiazide-like diuretic class due to the absence of high-quality head-to-head trials comparing these drugs.1,2

If available and affordable, selecting the thiazide-like diuretic chlorthalidone is reasonable.3 The benefits of chlorthalidone are better documented, including in the ALLHAT trial;3 the impact of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) on reducing risk for cardiovascular events has never been demonstrated against a placebo.4 Results from network meta-analyses suggest that, in addition to greater blood pressure-lowering potency, 3, 4 chlorthalidone reduces the risk of cardiovascular events by 21%.5 In one analysis, treating 10,000 patients for hypertension for five years with chlorthalidone would prevent 370 more events than using HCTZ.5

Another thiazide-like diuretic, indapamide, has also been shown to have greater blood pressure-lowering effects than HCTZ.4 Some publications have reported that, compared with HCTZ, indapamide may have less impact on glucose or lipid metabolism at doses for the same degree of blood pressure-lowering.4 However, most such publications have been sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, and the validity or real-world relevance of these findings is not established. Compared to placebo, indapamide has been shown among stroke patients to reduce cardiovascular events, and in combination with perindopril, to prevent CVD among the elderly, diabetics and post-stroke.6 – 8 Chlorthalidone and indapamide have not been compared head-to-head in terms effects on clinical events or mortality.

References

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management.2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-Guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2.

- The Allhat Officers and Coordinators for The Allhat Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in Moderately Hypercholesterolemic, Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Pravastatin vs Usual Care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(23):2998-3007. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2998.

- Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB, Tandon S, Sica DA. Head-to-Head Comparisons of Hydrochlorothiazide With Indapamide and Chlorthalidone. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1041-1046. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.114.05021.

- Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone Compared With Hydrochlorothiazide in Reducing Cardiovascular Events. Hypertension. 2012;59(6):1110-1117. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.112.191106.

- Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of Hypertension in Patients 80 Years of Age or Older.New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(18):1887-1898. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0801369.

- Chalmers J, Arima H, Woodward M, et al. Effects of Combination of Perindopril, Indapamide, and Calcium Channel Blockers in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Hypertension. 2014;63(2):259-264. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.02252.

- PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. The Lancet. 2001;358(9287):1033-1041. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06178-5.

Answer: Most major guidelines (including US, UK and Australian guidelines) no longer recommend beta-blockers across all age groups as first step drug therapy in the absence of a compelling non-BP indication.1 – 3 Beta Blockers are generally considered to be inadequate compared with first-line antihypertensive medications.

Meta-analyses have suggested that atenolol is ineffective for the primary prevention CVD events. A recent Cochrane Review of the effects of beta-blockers as first-line therapy for hypertension on morbidity and mortality endpoints concluded that initiating monotherapy with beta-blockers leads to modest CVD reductions, with little or no effects on mortality, and that the magnitude of benefit is inferior to that of other antihypertensive drugs.4 Another recent meta-analysis, which did not exclude trials in patients with baseline comorbidities, found that beta-blockers are inferior to other drugs for the prevention of major cardiovascular disease events, stroke, and renal failure.5 However, among younger patients, outcomes among those on beta blockers may be more favorable.6 Age-specific treatment protocols introduce additional complexity and are not considered in detail here.

Beta-blockers other than atenolol have been less well studied. Unlike atenolol, carvedilol is a nonselective beta blocker that also blocks the alpha-1 receptor, and is favored as a beta-blocker in some contexts, for example in the treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction. Nonetheless, carvedilol has not been studied in any major event-based, randomized controlled trial of blood pressure-lowering treatment.

References

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- National Heart Foundation of Australia. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults – 2016. Melbourne: National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2016. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/PRO-167_Hypertension-guideline-2016_WEB.pdf.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. 2011. PDF.

- Wiysonge CS, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Opie LH. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002003.pub5.

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957-967. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01225-8.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 1. Overview, meta-analyses, and meta-regression analyses of randomized trials. Journal of Hypertension. 2014;32(12):2285-2295. doi:10.1097/hjh.0000000000000378.

Answer: ACE inhibitors or ARBs are the preferred first-line agents for blood pressure treatment for hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined based on proteinuria (urinary albumin–to–creatinine ratio [UACR] >300 mg/g) and/or reduced kidney function (estimated glomerular filtration rage [eGFR] <60mL/min/1.73m2). These two renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers have proven benefits for prevention of CKD progression.1 – 4 For patients who cannot tolerate the common cough caused by ACE inhibitors, ARBs are as effective.5

In the AASK trial, among 1,094 U.S. African American patients with hypertensionand CKD, treatment with an ACE inhibitor reduced risk forCKD related outcomes by 22% compared with a beta-blocker and by 38%compared to a calcium channel blocker (CCB). (CKD related outcomes defined as kidney disease death, end-stage renal disease, or decline in eGFR). Overall, these results suggest that for every 100 hypertensive patients with CKD treated with an ACE inhibitor (in place of other medication classes) prevents 1-2 CKD-related outcomes. Cardiovascular disease or all-cause mortality benefits from an ACE inhibitor or and ARB compared to other anti-hypertensive agents have not yet been shown.2

ACE inhibitors, or ARBs can be used to control blood pressure in patients with diabetes and hypertension, though they do not appear be superior to alternative classes of antihypertensive therapy in patients without CKD.6 – 8 The most recent US hypertension guidelines equally recommend CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs and thiazide diuretics as first-line agents for people with diabetes and hypertension but without CKD.7.

References

- Cheung AK, Chang TI, Cushman WC, et al. Executive Summary of the KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International. 2012;99(3):559–569. Available at: . Available at: https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(20)31269-2/fulltext#.

- Wright JJT. Effect of Blood Pressure Lowering and Antihypertensive Drug Class on Progression of Hypertensive Kidney Disease: Results from the AASK Trial.Jama. 2002;288(19):2421. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2421.

- Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The Effect of Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition on Diabetic Nephropathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(20):1456-1462. doi:10.1056/nejm199311113292004.

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Investigators: Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: Results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2000;14(4):488. doi:10.1016/s1053-0770(00)70021.

- Barnett AH, Bain SC, Bouter P, et al. Angiotensin-Receptor Blockade versus Converting–Enzyme Inhibition in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(19):1952-1961. doi:10.1056/nejmoa042274.

- Whelton PK. Clinical Outcomes in Antihypertensive Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes, Impaired Fasting Glucose Concentration, and Normoglycemia. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(12):1401. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.12.1401.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Bangalore S, Fakheri R, Toklu B, Messerli FH. Diabetes mellitus as a compelling indication for use of renin angiotensin system blockers: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Bmj. 2016:i438. doi:10.1136/bmj.i438.

References

- Abraham HMA, White CM, White WB. The Comparative Efficacy and Safety of the Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in the Management of Hypertension and Other Cardiovascular Diseases. Drug Safety. 2014;38(1):33-54. doi:10.1007/s40264-014-0239-7.

- Dézsi CA. The Different Therapeutic Choices with ARBs. Which One to Give? When? Why? American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 2016;16(4):255-266. doi:10.1007/s40256-016-0165-4.

- Zheng Z, Lin S, Shi H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Telmisartan Versus Valsartan in the Management of Essential Hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2010;12(6):414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00287.x.

Table: Resolve to Save Lives equivalent standard doses of selected common antihypertensive medications

Disclaimer: There are limited studies comparing drug dose equivalency, and thus this table should be considered merely as guidance but not as absolute dose converter. After medication conversion, patients should be brought back soon for close follow-up blood pressure measurement and further titration.| CCB (these doses are likely to be equivalent to enalapril 5 mg) | Thiazide (these doses may be considered equivalent to amlodipine 5 mg and enalapril 5 mg) |

|---|---|

| Amlodipine 5 mg | Chlorthalidone 12.5 mg |

| Nifedipine 30 mg | Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg |

| ACEI (these doses are likely to be equivalent to amlodipine 5 mg) | ARB (these doses are likely to be equivalent to enalapril 5-10 mg and lisinopril 10 mg) |

| Benazepril 10 mg | Candesartan 8-16 mg |

| Captopril 37.5-50 mg | Eprosartan 200-400 mg |

| Cilazapril 1.25-2.5 mg | Irbesartan 75 mg |

| Enalapril 5 mg | Losartan 25-50 mg |

| Fosinopril 10 mg | Olmesartan 5-20 mg |

| Lisinopril 5-10 mg | Telmisartan 20-40 mg |

| Moexipril 3.75-7.5 mg | Valsartan 40-80 mg |

| Perindopril 2-4 mg | |

| Quinapril 10 mg | |

| Ramipril 2.5 mg | |

| Trandolapril 1-2 mg | |

References

- Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009 May 19;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. Review. PubMed PMID: 19454737; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2684577.

- Hall WD, Reed JW, Flack JM, Yunis C, Preisser J. Comparison of the efficacy of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in African American patients with hypertension. ISHIB Investigators Group. International Society on Hypertension in Blacks. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(18):2029-2034.

- Modernized Reference Drug Program Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs). https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/health-drug-coverage/pharmacare/rdp_decisiontree_aceis.pdf. Accessed 0715, 2019.

- Drug Comparisons -ACE Inhibitors – Med Equivalents. https://globalrph.com/medcalcs/drug-comparisons-ace-inhibitors-medication-equivalents/. Accessed 0715, 2019.

- McMurray J. The use of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) in clinical practice. Br J Cardiol 2016;23(suppl 1):S1–S16.

- Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers. https://globalrph.com/drugs/angiotensin-ii-receptor-blockers/. Accessed 0715, 2019.

- Cooney D, Milfred-LaForest S, Rahman M. Diuretics for hypertension: Hydrochlorothiazide or chlorthalidone? Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82(8):527-533.

- Peterzan MA, Hardy R, Chaturvedi N, Hughes AD. Meta-analysis of dose-response relationships for hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and bendroflumethiazide on blood pressure, serum potassium, and urate. Hypertension. 2012;59(6):1104-1109.

- Neaton JD, Grimm RH, Jr., Prineas RJ, Stamler J, Grandits GA, Elmer PJ, Cutler JA, Flack JM, Schoenberger JA, McDonald R and et al. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study. Final results. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study Research Group. JAMA. 1993;270:713-24.

- Zanchetti A, Omboni S and Di Biagio C. Candesartan cilexetil and enalapril are of equivalent efficacy in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11 Suppl 2:S57-9.

- McInnes GT, O’Kane KP, Istad H, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S and Van Mierlo HF. Comparison of the AT1-receptor blocker, candesartan cilexetil, and the ACE inhibitor, lisinopril, in fixed combination with low dose hydrochlorothiazide in hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:263-9.

- Oparil S. Eprosartan versus enalapril in hypertensive patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough. Current Therapeutic Research. 1999;60:1-14.

- Mimran A, Ruilope L, Kerwin L, Nys M, Owens D, Kassler-Taub K and Osbakken M. A randomised, double-blind comparison of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist, irbesartan, with the full dose range of enalapril for the treatment of mild-to-moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:203-8.

- Karlberg BE, Lins LE and Hermansson K. Efficacy and safety of telmisartan, a selective AT1 receptor antagonist, compared with enalapril in elderly patients with primary hypertension. TEES Study Group. J Hypertens. 1999;17:293-302.

- Prabowo P, Arwanto A, Soemantri D, Sukandar E, Suprihadi H, Parsudi I, Markum MS, Kabo P, Atmoko R and Prodjosudjadi W. A comparison of valsartan and captopril in patients with essential hypertension in Indonesia. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53:268-72.

- Holwerda NJ, Fogari R, Angeli P, Porcellati C, Hereng C, Oddou-Stock P, Heath R and Bodin F. Valsartan, a new angiotensin II antagonist for the treatment of essential hypertension: efficacy and safety compared with placebo and enalapril. J Hypertens. 1996;14:1147-51.

- Black HR, Graff A, Shute D, Stoltz R, Ruff D, Levine J, Shi Y and Mallows S. Valsartan, a new angiotensin II antagonist for the treatment of essential hypertension: efficacy, tolerability and safety compared to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:483-9.

- Grimm RH, Black H, Rowen R, Lewin A, Shi H, Ghadanfar M, Amlodipine Study Group, Amlodipine versus chlorthalidone versus placebo in the treatment of stage I isolated systolic hypertension, American Journal of Hypertension, Volume 15, Issue 1, 2002;15:31–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02224-5

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE MEDICATIONS: ADVERSE EFFECTS/SIDE EFFECTS

| Drug class | Conditions to monitor | Other considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors |

|

|

| ARBs |

|

|

| CCBs |

|

|

| Thiazide diuretics |

|

|

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Smellie WSA, Forth J, Coleman JJ, et al. Best practice in primary care pathology: review 6. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2006;60(3):225-234. doi:10.1136/jcp.2006.040014.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management.2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-Guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2.

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Adherence to guidelines for creatinine and potassium monitoring and discontinuation following renin–angiotensin system blockade: a UK general practice-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012818.

- Sinha AD, Agarwal R. Thiazide Diuretics in Chronic Kidney Disease. Current Hypertension Reports. 2015;17(3). doi:10.1007/s11906-014-0525-x.

- HEARTS Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: evidence-based treatment protocols. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/NMH/NVI/18.2). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Answer: 13 percent of people taking the thiazide-like diuretic chlorthalidone 12.5-25 mg daily developed hypokalemia in the ALLHAT trial.1 However, despite this observation, overall all-cause mortality was no different when compared to individuals taking the calcium channel blocker amlodipine or the ACE-inhibitor lisinopril. The authors of a subsequent analysis of hypokalemia in the ALLHAT trial concluded that “…clinicians should feel reassured that hypokalemia associated with low-to-moderate dose diuretics (12.5–25.0 mg of chlorthalidone a day) affected 13% of patients and was easily remedied…the cardioprotective actions of diuretic use are unaffected by consequent but treatable alterations in serum potassium.”1 Further, when a diuretic is combined with an ACEI, the risk of hypokalemia is greatly reduced.2

References

- Alderman MH, Piller LB, Ford CE, et al. Clinical Significance of Incident Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia in Treated Hypertensive Patients in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Hypertension. 2012;59(5):926-933. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.111.180554.

- Weinberger MH. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Enhance the Antihypertensive Efficacy of Diuretics and Blunt or Prevent Adverse Metabolic Effects. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1989;13. doi:10.1097/00005344-198900133-00002

Answer: The normal physiologic response to blood pressure lowering is to increase efferent arteriole constriction and restore glomerular perfusion pressure. ACE inhibitor and ARB blunt this response and may lead to decreased kidney filtration (decreased glomerular filtration rate) and kidney function. Clinical guidelines recommend monitoring serum creatinine response in a week or two following ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy and stopping therapy and further monitoring kidney function if the serum creatinine increases by more than 30% of the baseline value. Increases below this level are usually considered acceptable.1

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

Answer: When laboratory testing is unavailable, the safest option is to restrict medication prescription to metabolically neutral calcium channel blockers and increase these up to maximum doses if needed to control blood pressure. If additional medication classes are still needed, one may introduce other medication classes, but keep the doses of other classes of medications in the low- to mid- dose range. Higher doses of ACEIs, ARBs, and Thiazide/Thiazide-like diuretic should be avoided when laboratory testing is not available. Generally, most side effect incidence increases with medication dose.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND SPECIALIZED CARE FOR HYPERTENSION

Diabetes

Answer: There is considerable controversy concerning the ideal BP diagnostic threshold and treatment target for people with diabetes. Some recent guidelines recommend a goal of 140/90 mmHg for the general population, including those with diabetes.1, 2 Other current guidelines recommend more aggressive treatment goals with blood pressure (BP) targets of < 130/80 mmHg for people with diabetes.6 From a public health point of view, it is important to keep in mind that even using target of 140/90 mmHg, the control rate of blood pressure among hypertensives is 15% or lower in many countries. Thus, Resolve to Save Lives focuses on 140/90 mmHg as a target. Individual countries, areas, or providers can set lower limits.

The goal of treating hypertension in patients with diabetes is reduction of macrovascular and microvascular complications. Retrospective data analyses suggest an association between a lower BP and greater cardiovascular (CV) risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes, as well as declines in chronic kidney disease (CKD) . Although some note that such conclusions are not supported by randomized controlled trials*, when considering the weight of the evidence, it appears that more intensive blood pressure lowering may be beneficial for most people with diabetes.4

*The SPRINT trial demonstrated a benefit from intensive versus standard blood pressure lowering treatment in a trial that enrolled patients with high CVD risk and those with chronic kidney disease, but not patients with known diabetes or strokes.4, 5, 6, 7

References

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Jama. 2014;311(5):507. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-Guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2.

- American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management. Diabetes Care. 2016;40(Supplement 1). doi:10.2337/dc17-s012.