How we save lives / Healthier food / Salt reduction / Sodium reduction framework

Sodium reduction framework

This framework outlines the recommended components of a comprehensive dietary sodium reduction program, intended for governments and their partners. The framework also provides links to existing implementation tools, examples of successful programs and policies, and other resources.

You’ve been redirected. LINKScommunity.org is now part of resolvetosavelives.org.

- Introduction

- Governance

-

Surveillance

- Surveillance, monitoring & evaluation plans

-

Collect sodium indicator data

- Establish mean daily sodium intake

- Establish the main sources of dietary sodium

- Sodium content in key packaged food categories

- Establish the levels of iodine fortification and intake

- Assess public knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP)

- Innovative methods: household budget surveys to assess sodium intake and sources

- Program transparency and accountability

- Regular program review

- Packaged foods

- Food prepared outside the home

- Sodium added in the home

- Appendices and Acknowledgements

Introduction

This framework summarizes the recommended components of a comprehensive dietary sodium reduction program, and provides links to existing implementation tools, examples of successful programs and other resources.

It is designed to be used by governments and their partners in the planning, development and revision of dietary sodium reduction programs. It can also be used to standardize evaluation and review of these programs.

In some cases, as cited in this framework, sodium reduction is addressed through a stand-alone national strategy or program; however, sodium reduction can also be integrated into a broader noncommunicable disease or nutrition strategy. The components of this framework are relevant to both approaches. Cities and regions may also be able implement many of the strategies included in this framework and can work to complement national action.

The framework is organized into five major categories that make up a comprehensive sodium reduction program:

- Governance

- Surveillance

- Interventions for packaged foods

- Interventions for food prepared outside the home (i.e., restaurants, cafeterias)

- Interventions for sodium added at home (i.e., at the table and in cooking)

Several high-priority strategies are outlined for each type of intervention. In some cases, innovative or incompletely tested strategies are listed, particularly in areas where existing solutions are limited, evidence is still emerging, or research on impact has been mixed.

For each component of the framework, a list of resources is provided to guide readers in implementing the strategies. The resources are divided into 1) implementation tools: practical guides or toolkits, 2) other resources: scientific literature, background documents, relevant global guidance, etc., and 3) examples: real world case studies from cities and countries that have implemented these strategies in their local context. The resources and examples provided are not meant to be used as a comprehensive guide but aim to offer users suggestions for further reading on each topic. The resources are limited to resources published in English language.

The framework will be reviewed and updated over time; new resources and examples will be added periodically. Here you’ll find a brief survey where you can submit additional resources and suggestions.

This document is accompanied by a checklist and monitoring tool, found in Appendix 1.

Governance

A systematic and coordinated national strategy is the best way to make meaningful reductions in sodium consumption across the population. This section outlines the key steps required to develop and lead a strategic plan for sodium reduction, engage key stakeholders and decisionmakers, and minimize conflicts of interest.

Develop a comprehensive strategic plan

A strategic plan describes the approach the government and other stakeholders will take to lower dietary sodium. It should include: (1) vision and objectives, (2) main interventions and/or policies and their timelines, (3) communications plan, (4) monitoring and evaluation plan, and (5) key stakeholders (for more on stakeholders see Section 1.3).

Other aspects that may be included are an assessment of the political landscape and how different stakeholders will support the objectives. Ideally, the strategy is based on ‘SHAKE’, the World Health Organization (WHO) technical package to support population reduction in dietary sodium and/or regional WHO office strategies. The Pan American Health Organization and the Regional Office for Europe have regional packages/toolkits for salt reduction relevant to strategic planning.

While other countries’ strategies can be used as a model, countries should take into account the unique diets of their population, major sources of dietary sodium, and opportunities and challenges for reducing dietary sodium. The strategic plan should include an overall cost estimate and, ideally, costs per major intervention. The dietary sodium strategy can stand alone or be integrated into a broader noncommunicable disease or nutrition strategy. If dietary sodium reduction is part of a broader strategy, there need to be sufficient resources and priority allocated to successfully implement the sodium reduction-specific interventions.

Regardless of the approach, a successful strategy contains specific interventions to reduce sodium among the country’s primary dietary sources of sodium, whether it comes from packaged foods, food eaten outside the home (e.g., restaurants, canteens, street food), and/or food prepared and eaten in the home.

Successful strategies are usually multi-component approaches that combine a variety of policy measures and behavior change interventions along with a strong monitoring and evaluation component. Examples of comprehensive approaches include the United Kingdom’s salt reduction program as well as the Shandong-Ministry of Health Action on Salt and Hypertension (SMASH) program (He 2014, Xu 2020).

As part of strategic plan development, governments will need to understand the existing landscape, set goals, outline operational and organizational details, and assess costs and benefits. Some countries have formed sodium reduction working groups and/or advisory group to oversee the strategic plan. Further elaborations on these topics are provided in the following sub-sections 1A – 1D.

Implementation tools

World Health Organization. The SHAKE technical package for salt reduction. 2016.

Pan American Health Organization. Salt-Smart Americas: A Guide for Country-Level Action 2013.

Johns Hopkins University. Online Course on Global Sodium Reduction Strategies.

Other resources

Nourishing Database: World Cancer Research Fund International.

Examples

United Kingdom: He FJ et al. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health. J Hum Hypertens 2014;28:345-35

South Korea: Park H-K, Lee Y, Kang B-W, et al. Progress on sodium reduction in South Korea. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e002028.

Conduct a situational analysis (e.g., strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis)

A strategic plan describes the approach the government and other stakeholders will take to lower dietary sodium. It should include: (1) vision and objectives, (2) main interventions and/or policies and their timelines, (3) communications plan, (4) monitoring and evaluation plan, and (5) key stakeholders (for more on stakeholders see Section 1.3).

Other aspects that may be included are an assessment of the political landscape and how different stakeholders will support the objectives. Ideally, the strategy is based on ‘SHAKE’, the World Health Organization (WHO) technical package to support population reduction in dietary sodium and/or regional WHO office strategies. The Pan American Health Organization and the Regional Office for Europe have regional packages/toolkits for salt reduction relevant to strategic planning.

While other countries’ strategies can be used as a model, countries should take into account the unique diets of their population, major sources of dietary sodium, and opportunities and challenges for reducing dietary sodium. The strategic plan should include an overall cost estimate and, ideally, costs per major intervention. The dietary sodium strategy can stand alone or be integrated into a broader noncommunicable disease or nutrition strategy. If dietary sodium reduction is part of a broader strategy, there need to be sufficient resources and priority allocated to successfully implement the sodium reduction-specific interventions.

Regardless of the approach, a successful strategy contains specific interventions to reduce sodium among the country’s primary dietary sources of sodium, whether it comes from packaged foods, food eaten outside the home (e.g., restaurants, canteens, street food), and/or food prepared and eaten in the home.

Successful strategies are usually multi-component approaches that combine a variety of policy measures and behavior change interventions along with a strong monitoring and evaluation component. Examples of comprehensive approaches include the United Kingdom’s salt reduction program as well as the Shandong-Ministry of Health Action on Salt and Hypertension (SMASH) program (He 2014, Xu 2020).

As part of strategic plan development, governments will need to understand the existing landscape, set goals, outline operational and organizational details, and assess costs and benefits. Some countries have formed sodium reduction working groups and/or advisory group to oversee the strategic plan. Further elaborations on these topics are provided in the following sub-sections 1A – 1D.

Implementation tools

World Health Organization. The SHAKE technical package for salt reduction. 2016.

Pan American Health Organization. Salt-Smart Americas: A Guide for Country-Level Action 2013.

Johns Hopkins University. Online Course on Global Sodium Reduction Strategies.

Other resources

Nourishing Database: World Cancer Research Fund International.\

Examples

United Kingdom: He FJ et al. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health. J Hum Hypertens 2014;28:345-35

South Korea: Park H-K, Lee Y, Kang B-W, et al. Progress on sodium reduction in South Korea. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e002028.

Establish and demonstrate the potential benefits of dietary sodium reduction, including cost-effectiveness

Sodium reduction strategies save lives and are cost-effective. Asaria et al. estimated that in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) a 15% reduction in dietary sodium intake over ten years would prevent 8.4 million deaths (Asaria 2007) and cost only $0.04 to 0.32 per person. At the global level, numerous analyses have found that millions of lives can be saved by dietary sodium reduction (Kontis 2019); there are many country-specific cost-effectiveness studies, which can be enormously useful for securing political buy-in and resources. For example, cost-effectiveness data showing a potential 78-to-1 return on investment in South Korea was critical to winning support for the country’s salt reduction program (Park 2020). In the absence of a local study, countries can use tools such as the Global Burden of Disease to estimate how many lives are lost to high sodium intake.

Implementation tools

World Health Organization. Choosing interventions that are cost effective (WHO-CHOICE).

Other resources

Resolve to Save Lives. Tool to calculate lives saved by cardiovascular health interventions.

World Health Organization. Saving Lives, spending less. 2018.

IHME. Global Burden of Disease Website.

Examples

Set short, mid- and long-term sodium intake goals

Establish long-term and feasible mid-term goals for sodium intake, consistent with the WHO goal of adults consuming less than 2,000 mg sodium/day and the commitments made by many countries to reduce sodium intake by 30% by 2025, following the 66th World Health Assembly in 2013. Defined public goals and timelines will help guide program activities, assess progress and enhance accountability.

Acquired taste for sodium, use of sodium as a preservative, changing people’s usual practices in food preparation, length of time to adapt tastes for sodium, as well as eating habits and use of salt alternatives should be considered when creating feasible short (e.g., 2 years, 10% reduction), mid- (e.g., 5 years, 20% reduction) and long-term targets and goals (e.g., 10 years, majority of population consumes less than 2000mg sodium/day). It is recommended to have a mid-term (e.g., 3-5 year) goal that is feasible and based on a national situational analysis (Section 1.1a). Targets and timelines are important for evaluating the progress of the program over time and for assessing the need for revising interventions and policies.

Examples of mid- and long-term program goals

| Location | Short or Mid-term goal | Long-term goal |

| Global | Reduce sodium intake by 30% by 2025 | Maximum adult intake of 2,000 mg/day |

| Vietnam | Reduce the average salt consumption of adults to 7 g/day between 2018 – 2025. | —- |

| Finland | Reduce salt intake by 20% between 2012-2020. |

Max salt intake:

|

| United States National Salt Reduction Initiative* |

Reduce population sodium intake by 20%, through a reduction in sodium in US packaged and restaurant foods by 25% by from 2009 to 2014 | Maximum limit of 2,300 mg/day |

*This program is a partnership of organizations and health authorities from across the United States, convened by the New York City Health Department, that set voluntary salt reduction targets

Other resources

World Health Organization. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. 2012.

Examples

South Africa: South Africa. National Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases 2020-2025

Finland:Nutrition Commitments: Salt

Israel: Ministry of Health of Israel. The National Sodium Reduction Program.

Establish an operational plan with organizational structure and budget

The findings of the situational analysis (Section 1a) can be used to determine the most appropriate interventions and timelines to meet the established goals (Section 1.1c). Interventions that address the most prominent sodium sources should be included (see Sections 3-5 for potential interventions). Where these are unknown, surveillance activities to determine the main sources of sodium (Section 2.2b) should be conducted before selecting specific interventions.

It may also be helpful to review examples of existing sodium reduction interventions from countries around the world. A few organizations provide regularly updated databases or websites that track country examples of sodium reduction policies and interventions. These include the World Cancer Research Fund International’s NOURISHING Database, and the World Action on Salt, Sugar, and Health’s (WASSH) website.

Based on the strategic plan (Section 1.1), the operational plan assigns specific tasks and timelines for reducing dietary sodium to various stakeholders, defines leadership, and establishes accountability. The operational plan should create a structure to optimize implementation and establish a timeline for regular program review. The structure should facilitate smooth long-term interactions of the various stakeholders, linking the people and organizations that need to work together or who have interdependent work to achieve the short, mid- and long-term goals. See Section 1.3 for more detail on stakeholder engagement.

An operational plan should also include the budget necessary to carry out the specific activities in the plan. Costs could include: baseline and ongoing data collection on sodium intake, sodium sources, and sodium levels in foods; public education campaigns; policy development and implementation; human resources; establishing a working group or network, etc.

Implementation tools

World Health Organization: The One Health Tool for Costing Interventions.

Other resources

World Cancer Research Fund International. NOURISHING Database.

Design and conduct an advocacy strategy

Advocacy—activities to support and influence relevant decision-makers to take the necessary actions to promote a salt reduction strategy—will be critical throughout the design and implementation process. These activities may seek to win general support for salt reduction from the government (including commitments to reduce salt intake in the country and prioritization of salt reduction within the government agenda); it may also aim to convince government officials to support and promote a specific policy that will lead to a reduction in salt intake (e.g., adopting salt targets for packaged food, front-of-pack labeling, etc.)

Advocacy is frequently led by civil society groups or other non-profit or academic institutions. Involvement from these groups, and the constituencies they represent, expands the scale and diversity of support for sodium reduction measures; their visible backing for sodium reduction policies can counter opposition from industry and support government stakeholders to take action. Advocacy may also be conducted within the government itself; program leaders may need to convince other officials in order to obtain buy-in within the Ministry of Health; the Ministry of Health may need to obtain buy-in from other agencies such as Ministries of Trade or Finance that are traditionally less focused on health outcomes.

Before designing an advocacy strategy, ensure there is a clear definition of specific goals for sodium reduction (See Section 1.1c), and outline the changes that need to occur for the salt reduction strategy to move forward (See Section 1.1d). Once goals are defined, review findings from the situational analysis (Section 1.1a) to better understand the political and social contexts and identify opportunities as well as threats (e.g., SWOT analysis) for getting sodium reduction onto the current public health agenda, if it is not yet a priority. Also determine what tools and resources are available (e.g., existing data, previous sodium reduction experience and lessons learned in-country or from other countries, financial resources). In most cases, current data on sodium intake, sources, and/or content of foods is important for bringing sodium reduction into the public agenda and convincing stakeholders to take action. Identify key research gaps (refer to the situational analysis) and determine methods and actors/groups to fill these gaps.

Next, build a coalition or network of organizations interested in salt reduction or its related policies. This should start with a stakeholder analysis that examines various actors’ potential roles, level of support (or opposition), and power/influence to determine who to involve to make progress on each goal. Once allies (government bodies, civil society, NGOs, researchers, etc.) are identified and incorporated into the network, the network can meet to agree on common actions (media or political actions), amplify advocacy messages, and ensure a coherent call to action among diverse groups, such as children’s rights, sustainable food systems groups, obesity prevention organizations. Organizational priorities and agendas will vary, but working to find common long-term goals and to highlight partner achievements can encourage collaborative partnerships.

Finally, determine the target audience of the advocacy strategy. This should also derive from the results of the stakeholder analysis, in particular who has the power to make the necessary changes to achieve the identified goals (it may be a different decision-maker or group of decision-makers for each goal). Target audiences often include ministries of health, education, agriculture, and finance, food and drug administrations, and legislators.

Effective advocacy activities take into account what matters to the target audience and tailor arguments to appeal to that audience. Some audiences may find information about the negative health impacts of sodium and the health benefits of policy action compelling; others may find information about cost-effectiveness persuasive. For some decision makers, public and/or media support for the issue may also be critical (especially in the face of industry opposition). Also, consider how sodium reduction may support other policy goals, such as improving children’s health, providing nutritious school food, or supporting local agriculture. In general, it is important to anticipate and address potential concerns from stakeholders and build arguments to address them.

Once you have the building blocks in place, a comprehensive advocacy strategy can be created.This strategy can include many forms of advocacy: strong advocacy efforts include multiple complementary activities.

Advocacy activities commonly conducted by civil society and other groups include:

- Providing background research, fact sheets or policy briefs to decision-makers

- Arranging in-person meetings, phone calls, briefings or workshops with government stakeholders

- Testifying at hearings or presenting at conferences on the health harms of excess sodium and existing successful models in other countries/cities

- Generating relevant local data (e.g., data on sodium content of commonly consumed packaged food products, etc.) and designing advocacy material to inform decision-makers and/or the public about relevant data

- Conducting public awareness campaigns to build public support (using paid mass media, social media, and other channels to reach the public and other stakeholders)

- Contact journalists and/or provide journalist trainings to raise awareness about the importance of salt reduction and advocate for specific action where relevant

- Pursuing earned media coverage (e.g., newspaper or television mentions, placement of op eds in support of sodium reduction strategies)

- Identifying champions that may help get the issue into the public agenda

Advocacy activities commonly conducted by government organizations include:

- Convening workshops and presenting evidence on the need for and benefits of sodium reduction

- Sharing progress reports, publishing press releases, or participating in multi-sectoral mid-term reviews with policymakers to highlight the impact of sodium reduction interventions that are underway (progress reviews also provide an opportunity to address concerns or challenges identified during policy implementation)

Implementation tools

Global Health Advocacy Incubator. Advocacy Tools. Political Mapping tool. (free registration required)

Other resources

Examples

Engage stakeholders

Throughout the process of developing and implementing a national sodium reduction strategy, numerous types of stakeholders will be engaged (see Section 1.3c for examples). This section describes key steps to identifying stakeholders through a stakeholder analysis, engaging stakeholders, and building support among important stakeholder individuals and groups.

Set the agenda

To set the agenda and garner key stakeholders and decision makers’ support for implementing a sodium reduction strategy, a fact sheet and call to action (e.g., Campbell 2016) developed by supportive organizations and individuals can be helpful. The fact sheet should emphasize the current levels of sodium intake, the high rates of premature death and disability caused by high dietary sodium and should be tailored to the specific country using available data, such as national-level data from the Global Burden of Disease. The WHO Sodium Country Score Card, which tracks countries’ progress in implementing legislative and other measures to reduce dietary intake of sodium, can help countries review progress identify gaps, and compare with other countries. Health economic analyses can play a critical role in winning political support given the high returns on investment and cost savings from dietary sodium reduction programs (Section 1.1b). The fact sheet can also provide examples of successful salt reduction policies and interventions.

Implementation tools

Other resources

World Health Organization. The SHAKE technical package for salt reduction. 2016.

Examples

Establish decisionmaker support

Visible, public leadership by a senior government official, such as a Minister of Health, features in many successful dietary sodium strategies. The program needs strong governmental agency secretariat support and budget to provide resources (e.g., financial, staffing) to develop and implement key policies, monitor and evaluate the program and support long-term stakeholder engagement.

Identify and engage key stakeholders

A stakeholder analysis should be conducted to identify the key groups and individuals to engage. Key stakeholders come from many sectors, including government, non-governmental organizations, civil society organizations, academia, media, and the food industry. Stakeholders have different roles to play and should have different levels of influence on the process. The operational plan described in Section 1.1d can outline the key roles and responsibilities of the stakeholders.

Strong government commitment and oversight is needed for success. Ideally, there should be involvement from multiple government departments, including those responsible for nutrition and food regulations, non-communicable disease prevention, surveillance, food procurement, trade, and marketing, advertising, and broadcasting regulations. Nutritionists, dieticians, and other nutrition-specific program experts will also be useful to engage.

Civil society organizations can be important champions of the work. They can help to expand the scale and diversity of support for sodium reduction activities and keep the pressure on government to act. In many countries, civil society may formally support and assist the government with drafting, reviewing or providing comments, and monitoring policies. Key types of organizations to involve include health advocates (e.g., heart or kidney foundations/associations, consumer protection associations), public health and medical associations (e.g., cardiovascular societies, nutrition societies, family physicians, nurses, dietitians), academics (e.g., epidemiologists, nutritional scientists), and education professionals (e.g., culinary schools, health staff in schools). Engaging global organizations may be helpful to gain insight from ongoing sodium reduction programs in other jurisdictions. Well-known role models (e.g., athletes, celebrities, entrepreneurs, chefs) may also play a role in raising awareness and building support for salt reduction programs and policies.

While the food industry is a stakeholder in many sodium reduction policies and should have a structured opportunity for input on specific policies that impact the industry, this process needs to be transparent and governed by a strong conflict of interest policy (See Section 1.4).

See Section 1.3 for further details on stakeholder advocacy.

Implementation tools

World Health Organization. Stakeholder Analysis.World Health Organization. Accelerating Nutrition Improvements (ANI) Mapping of stakeholders and nutrition actions in three scaling-up countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Report of a meeting. 2014.

Other resources

Examples

Pan American Health Organization: PAHO. Salt-Smart Americas: A Guide for Country-Level Action. 2013.

South Africa: Webster J. et al. South Africa’s salt reduction strategy: Are we on track, and what lies ahead? S. Afr. med. j. 2017; 107.1. (Report of a stakeholder meeting in South Africa)

Victoria, Australia: Rosewarne E et al. Stakeholder perspectives on the effectiveness of the Victorian Salt Reduction Partnership: a qualitative study. BMC Nutr 7, 12 (2021).

Counter scientific opposition

In some cases, there may be arguments against sodium reduction by members of the scientific community or other stakeholders. It is important to note that scientific controversy has been created by a small group of scientists who suggest that low levels of sodium can increase cardiovascular mortality. These arguments are based on observational studies that rely on lower quality methods of measuring sodium intake. Other problems in the literature include reverse causality, lack of rigor in research, conflicts of interest and commercial bias (Cobb 2020, Campbell 2021). Rigorous reviews of the evidence for sodium reduction, such as those completed by the National Academies of Medicine or the European Food Safety Authority, have consistently concluded that sodium intake should be limited to 2,000 or 2,300 mg/day to protect cardiovascular health. Stakeholders, especially those from academia, can be involved to counter scientific opposition from other stakeholders using documented high quality, rigorous research from unbiased sources, emphasizing the clear impact of high sodium intake on blood pressure levels and the benefits of sodium reduction on cardiovascular health outcomes.

Other resources

Mitigate conflicts of interest

The food industry is one of the largest in the world (and a dominant industry in many countries); it has long opposed policies and regulations that could impact its profits. Industry associations at both the global and national level represent the commercial interests of the food industry and will likely oppose policies that reduce sodium in their products. The food industry has created and funded organizations to evaluate science from an ‘industry-friendly’ perspective by creating educational programs and hiring scientists and clinicians to represent industry interests and often funds their meetings and presentations (Campbell 2021). The source of funding may not be disclosed or can be misrepresented (by using a third-party organization, such as the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI), or funding to an academic or health organization).

Creating a structured approach for industry and people with industry ties to comment on a draft policy, without including them in policy development or final decision-making, is strongly recommended. There are several policies and/or regulations that can reduce the impact of conflicts of interest during the policy process. Best practice is to: 1) Define conflicts of interest broadly and comprehensively; 2) Require written disclosure of financial interests at regular intervals (e.g., annually) by all parties involved; 3) Include groups acting in the public and public health interest (e.g., academics, civil society, etc.) as part of the policy process; and 4) Develop strategies for mutual accountability and monitoring.

Other resources

The SUN Movement Toolkit for Preventing and Managing Conflicts of Interest. 2014

The New York Times. Jacobs A. A shadowy industry Group Shapes food policy around the world. 2019.

Global Health Advocacy Incubator (GHAI). Countering Industry Interference: Industry Watch Resources. Includes:

- Global Health Advocacy Incubator (GHAI). Behind the Labels Big Food’s War on Healthy Food Policies. November 2021.

- GHAI: Front of Package Labeling – Industry Arguments: Counter Messages and Evidence. August 2021.

- Global Health Advocacy Incubator (GHAI). FOPL – preparing for and responding to international trade law arguments. 2020.

- Industry Interference Policy Briefs No. 1: Industry Interference in Food Policy.

Surveillance

A comprehensive strategic plan for sodium reduction will require a robust surveillance strategy to monitor key sodium indicators, evaluate progress and impact and optimize the plan over time. Data should be made publicly accessible in order to ensure transparency and hold the government accountable to its goals.

Develop surveillance, monitoring and evaluation plans

A surveillance, monitoring and evaluation plan should establish ways to measure progress toward the goals outlined in the strategic plan (Section 1.1), including:

- Baseline and follow-up measurements of average population sodium intake

- Major sources of dietary sodium and the levels of sodium in foods targeted by the program

- Monitoring of interventions, which can include process indicators to monitor whether actions have been implemented in the timeframe outlined in the operational plan

- Interim indicators, such as the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of segments of the public, which can contribute to monitoring program progress, barriers, or facilitators (see Section 2.2e).

The plan should outline the frequency of measuring key indicators and should include the required budget, the necessary research and laboratory capacity, and the steps required to build capacity if needed. It is ideal to assess all population indicators in a representative sample with adequate statistical power to examine changes over time and among specific sub populations of interest (e.g., different ethnic populations who may have unique dietary patterns, men vs. women, and key age groups).

Initiatives to reduce dietary sodium can begin while baseline data is being collected, provided the major sources of dietary sodium are known (understanding that the intervention may impact the baseline data).

Surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation plans are often developed and overseen by the sodium reduction advisory or working group; however, in many cases academic institutions or other research groups may be involved. It may be useful to have an independent group conducting surveillance activities. Surveillance of sodium intake and sources of salt can also be built into regularly schedule population surveys, such as WHO STEPS survey or the Demographic and Health Surveys. Additionally, ongoing monitoring and evaluation can be built into existing systems, for example, within health services or food safety systems.

The checklist in Appendix 1 can be used to structure a regular program review

Other resources

World Health Organization. SHAKE the salt habit: The SHAKE technical package for salt reduction. 2016. (see section on: Surveillance: Measure and Monitor Salt Use)

WHO EURO. Accelerating salt reduction in Europe: a country support package to reduce population salt intake in the WHO European Region. 2020.. (see sections 2.7 and 3)

Pan American Health Organization. Salt-Smart Americas. A Guide for

Country-Level Action. 2013.

Examples

Collect sodium indicator data

The Surveillance, Monitoring, and Evaluation Plan (Section 2.1) will outline indicators that should be established at baseline and repeatedly measured throughout and after interventions take place. This section describes the key indicators to measure, including mean sodium intake; dietary sources of sodium; sodium content in packaged foods; iodine intake and fortification levels; and knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sodium.

Establish mean daily sodium intake

Mean dietary sodium provides information on intake relative to the WHO recommended maximum adult intake of 2,000 mg of sodium (5 g salt) per day and sets the baseline for measuring future progress. Assess sodium intake through a nationally representative, adequately powered survey.

Several different methodologies can be used for measuring mean daily sodium intake. While more expensive and labor-intensive than other methods, the most accurate method is to collect complete 24-hour urine samples and analyze them for sodium and creatinine. (Although single 24-hour urine collections are not a reliable indicator of an individual’s usual sodium intake, the method is accurate on a population basis if the urine collections are complete.).

Measurement of sodium and creatinine using spot urine samples can be used to estimate average population 24-hour sodium intake. This method is used as part of the WHO STEPS survey and is less expensive and technically much easier than 24-hour urine collection. While it appears to be an acceptable way to assess the average population sodium intake at a single time point, using spot urine samples to assess change in average population sodium intake over time is considered to be less reliable (though research is still ongoing). Spot urine samples also underestimate the distribution of sodium intake. Ideally, if using spot urine samples, there should be a validation sub-sample where 24-hour urine samples are collected.

Dietary recall surveys (e.g., one or more 24-hour recalls) are another option for measuring sodium intake. Validity is highly dependent on the recall ability of the respondents, completeness and accuracy of the food database used to support the survey, and it is an unreliable method for assessing sodium added during cooking or at the table. While sodium intake can be significantly underestimated using this method (especially where food databases are less reliable or large proportions of sodium are added at home, in cooking or at the table), one advantage of the dietary recall survey is that it also assesses the dietary sources of sodium and provides information that is valuable for other, complementary nutrition initiatives. In some cases, surveys also quantified sodium intake using food weighing methods (Du 2014).

Implementation tools

PAHO: Protocol for Population Level Sodium Determination in 24‐hour Urine Samples. 2010.

Other resources

World Health Organization. WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS) (see link for data collection instruments, user manual, and country reports)

Examples

Establish the main sources of dietary sodium

Dietary sodium is typically consumed from three distinct sources: sodium added to packaged food during manufacturing, sodium added to food consumed outside the home (e.g., restaurants, street food vendors, cafeterias/canteens), and discretionary sources (sodium added in the home, either during cooking or while eating). The main dietary sources of sodium are usually established by dietary recall surveys or food frequency questionnaires (FFQ). The validity of the survey results is highly dependent on the recall ability of the respondents and the accuracy and completeness of the sodium content of the foods in the database used to support the survey. It is important to have data for the sodium content in targeted primary sources of sodium in order to track reductions over time (in addition to broader data on population sodium intake). Developing and updating a database to track the sodium content of foods is important for tracking changes that may occur during the intervention. If the intervention is successful, there may also be changes in the main dietary sources of sodium.

If it is not possible to pinpoint the main dietary sources of sodium, understanding the main components of the diet (regardless of the sodium content) can help plan and prioritize interventions.

Implementation tools

WHO/PAHO: A review of methods to determine the main sources of salt in the diet. 2010.

Examples

China, Japan, UK, U.S.: Anderson CA, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. JADA 2010 May 1;110(5):736-45.

Identify the sodium content in key packaged food categories

Many of the well-defined, evidenced-based policies to reduce sodium intake focus on packaged foods. A crucial starting point for these policies is to establish a database including key categories of packaged foods and their sodium levels. The easiest way to build this type of database is to use the sodium content from nutrition labels. Appendix 3 provides guidance on developing a food database via visits to food retail stores. In some settings, most of the data can be collected efficiently from online sources, and commercial groups may sell data on the nutrient content of packaged foods. Various technologies have been developed to assist collection of packaged food label data, such as applications that allow for simpler in-person data collection (e.g., FLIP, FoodSwitch), web-scraping techniques (e.g., foodDB), or crowd-sourcing (e.g., FoodSwitch).

While the Food and Agriculture Organization and WHO’s Codex Alimentarius (“Codex”) recommends that sodium be required on packaged food nutrient declarations, many countries still do not require it. See Section 3.2a for specific recommendations on mandatory nutrient declaration labeling. In addition to collecting label data, it may be necessary to measure the sodium level of selected foods for monitoring; in some countries, labeled nutrient content can be inaccurate even if labeling is required. Government food authorities can also create a national database of packaged foods by making it mandatory for food industry to submit nutritional content (including sodium) of packaged foods when applying for product registration.

Implementation tools

Resolve to Save Lives. Appendix 3. Instructions for developing a food database.

Other resources

FAO and WHO. International food standards (FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius).

WHO EURO. Using third-party food sales and composition databases to monitor nutrition policies. 2021.

The George Institute for Global Health. FoodSwitch mobile application. (See for data collection tool) and the Global Food Monitoring Initiative (see for sample protocols)

Examples

Latin America/Caribbean: Arcand J et al. Sodium Levels in Packaged Foods Sold in 14 Latin American and Caribbean Countries: A Food Label. Nutrients. 2019;11, 369.

Establish the levels of iodine fortification and intake

Once a major global public health concern, iodine deficiency has been largely overcome in many countries by iodizing salt. The levels of iodine added to salt should be based on sodium intake in the population; more iodine can be added as sodium intake falls, allowing for optimum intake of both nutrients. Iodine fortification and sodium reduction programs are thus mutually compatible and should be coordinated wherever possible in terms of both advocacy and communication (to policymakers, the food industry and the public) and to program surveillance and evaluation.

Iodine intake can be monitored along with sodium, with particular attention to the populations most vulnerable to iodine deficiency: children and pregnant women.Iodine is typically assessed using spot urine samples but, like sodium, can be more accurately measured using complete 24-hour urine samples.

Other resources

Examples

China: He FJ, et al. Effect of salt reduction on iodine status assessed by 24 hour urinary iodine excretion in children and their families in northern China: a substudy of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016 Sep 1;6(9):e011168.

South Africa, Ghana: Menyanu E et al. Salt-reduction strategies may compromise salt iodization programs: Learnings from South Africa and Ghana. Nutrition 2021; 84: 111065.

Assess public knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP)

Assessing the public’s knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) relating to dietary sodium can help in the design and monitoring of behavior change and education programs and provides a baseline of the public’s receptivity to and support of potential policy interventions. The result of repeated KAP surveys can be used to track the effectiveness of mass media campaigns, educational interventions and policy changes. However, monitoring changes in practice through KAP indicators cannot replace a quantitative assessment of sodium intake; many projects have seen changes in KAP survey indicators without changes to sodium intake.

KAP surveys can also be designed to assess the food industry’s knowledge, willingness and intention to change, the support or challenges from the health and scientific sector and from policymakers.

Implementation tools

Other resources

Examples

South Africa, Ghana: Menyanu E et al. Salt Use Behaviours of Ghanaians and South Africans: A Comparative Study of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices. Nutrients 2017, 9, 939.

Ethiopia: Survey on salt consumption knowledge, attitudes and practices and blood pressure in Ethiopia

Innovative methods: household budget surveys to assess sodium intake and sources

A small number of countries (Brazil, Poland, Slovenia, and Costa Rica) have used Household Budget Surveys (HBS) to estimate average sodium consumption and major dietary sources of sodium. The method is rapid and inexpensive, with most countries collecting data through HBS every 4-5 years. There is inadequate research at this time to assess the generalizability or reliability of using this approach.

Program transparency and accountability

Once established, indicators for reducing dietary sodium should be made easily and publicly accessible to encourage transparency and accountability for the program. Making data available to the health and scientific community for analysis and dissemination applies pressure on the food sector to meet sodium targets in their products and on program leaders to meet overall program goals. Consumer protection groups can play an important role in ensuring accountability through communications with the public.

Other resources

Examples

Canada: Health Canada’s Trans Fat Monitoring Program (not sodium but excellent example).

Regular program review

Sodium program operational plans (Section 1.1d) need to be reviewed and adjusted to account for lessons learned. Regular program review (e.g., annually) by the working group or other body identified in the strategic plan should assess progress towards targets and also take into account overall trends in dietary intake and sources.

Interventions for packaged foods

Addressing sodium consumption from packaged foods is an important component of a salt reduction strategy where packaged food consumption is high or growing. Regulatory approaches are typically most effective for reducing sodium in packaged foods (Hyseni 2017). Multiple strategies exist for reducing sodium intake from packaged foods, including setting targets to lower the sodium content in packaged foods, mandating accurate nutrition labels, fiscal policies (taxation of high-sodium or junk foods/HFSS foods (high fat, sugar, salt)) and subsidies to incentivize consumers to make healthier choices), and limits on what foods can be marketed/advertised to children. One strategy to lower the sodium content of packaged foods without altering taste is the partial substitution of salt with low-sodium salt. Low-sodium salt is discussed further in Section 5.2.

Nutrient profiling models

Nutrient profile models classify foods according to their nutritional quality. Government-led nutrient profiling is critical to the implementation of nutrition policies such as front-of-pack labels, fiscal policies and marketing regulations on unhealthy foods. Industry-developed labeling programs that rely on nutrient thresholds are part of marketing a company’s products and are not appropriate for public health interventions. Nutrient profiles specify thresholds for each nutrient (most include only harmful nutrients such as sodium, sugar and saturated fat). Nutrient thresholds may or may not vary by category. Some nutrient profile models focus on identifying foods that people should avoid, some on identifying better-for-you foods, and others on creating a system to rate foods based on overall healthfulness. The type of nutrient profile will depend on how the model will be used. For instance, in marketing restrictions, a nutrient profile model establishes thresholds above which products cannot be marketed to children, whereas certain front-of-package labels classify foods into multiple categories (e.g. red, yellow or green for traffic light labels) and therefore require a nutrient profile model that provides multiple thresholds.

Countries can often utilize existing nutrient profile models from another country with effective nutrition policies, as long as the model can be adapted to fit the new context based on the food categories commonly consumed. The WHO has developed regional nutrient profile models, mostly for restricting marketing of unhealthy food to children. These may be adapted for other policies as well (see the resources section below for links to the WHO nutrient profile models).

Other resources

Global Health Advocacy Incubator. Nutrient Profile Models Position Paper. 2024

WHO Nutrient Profiling: Report of a WHO/IASO Technical Meeting

WHO regional nutrient profile models:

- WHO Nutrient profile model for the WHO African Region

- Pan American Health Organization nutrient profile model

- WHO Nutrient profile model for the marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverages to children in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region

- WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model

- WHO nutrient profile model for South-East Asia Region

- WHO nutrient profile model for the Western Pacific Region

Examples

Bogotá, Colombia: Mora-Plazas M, et al. Nutrition Quality of Packaged Foods in Bogotá, Colombia: A Comparison of Two Nutrient Profile Models. Nutrients. 2019 May 4;11(5):1011.

* Interventions identified as WHO ‘best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases.

^ Interventions identified as Recommended priority actions in: Ide N et al. Priority actions to Advance Population Sodium Reduction. Nutrients 2020.

Labeling interventions for packaged foods

Labeling of packaged foods for sodium content (and other nutrients with critical health impact) provides consumers with information so they can avoid less healthy products and select healthier products; labeling also stimulates industry reformulation and new product development.

Mandatory nutrient declaration labels*

At a minimum, national regulations for packaged food labels should require a list of ingredients in descending order of weight and a nutrient declaration including calories, sodium, potassium, sugar, trans fat, and saturated fat (accurate to within 20%). Independent monitoring of the accuracy of labels is important. According to CODEX guidelines, information on nutrient content should be numerical; for example, expressed in g per 100 g or per 100 ml or per package if the package contains only a single portion. Appropriate back of package labeling alone will not lead to lower sodium intake or lower sodium content of packaged foods but is foundational to other packaged food interventions.

Other resources

FAO and WHO. Food Labelling. Fifth Edition. 2007.(See section: ‘Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling CAC/GL 2-1985′)

Examples

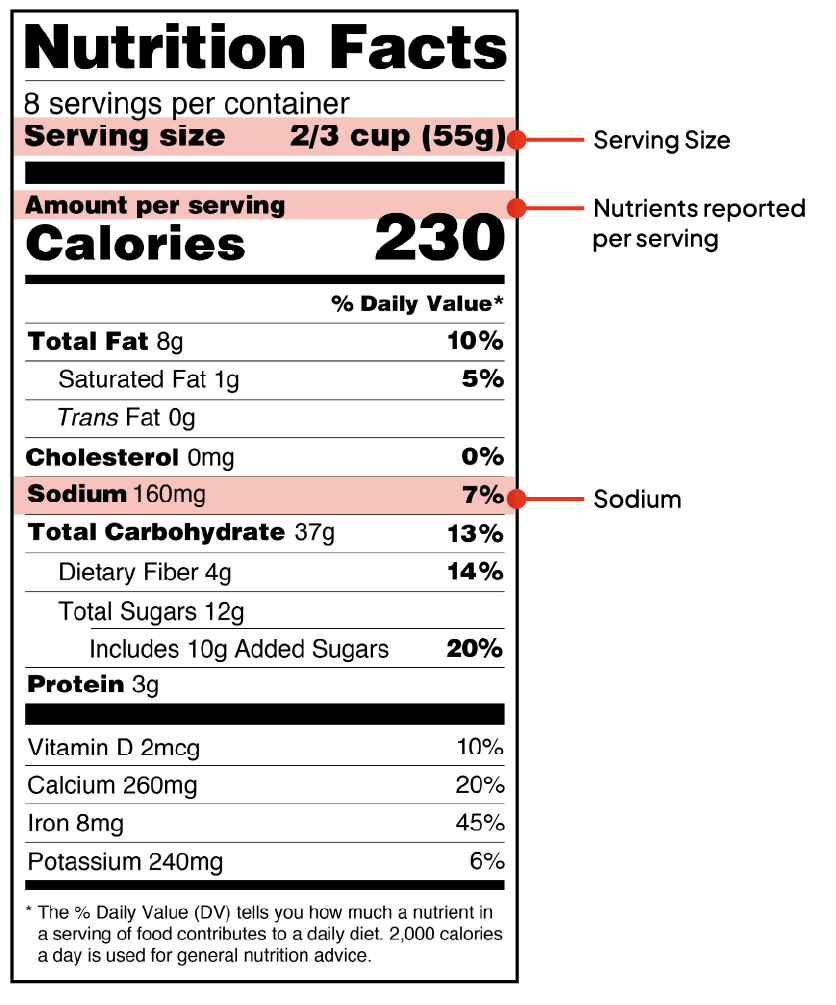

United States: US FDA. How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label.

Regulations restricting health claims on food packages

Food manufacturers will often put a health or quality claim on food packages or other marketing materials; these claims may be regulated by the government. CODEX guidelines offer the following definitions for claims on sodium content:

- Low sodium = not more than 0.12 g per 100 g

- Very low sodium = 0.04 g per 100 g

- Sodium free = 0.005 g per 100g

However, even when regulated, many health claims can be difficult for consumers to understand and may create a “health halo effect,” misleading consumers to believe a product is healthy when it is not. For example, a claim on a package that a food contains “low sodium” may lead a consumer to believe it is healthy when in fact it may be high in saturated fat or sugar. At minimum, health claims should not be allowed on packages of food that contain high quantities of sodium, sugar or saturated fat (or that are otherwise unhealthy based on the government’s nutrient profile).

Other resources

FAO and WHO. Food Labelling. Fifth Edition. 2007.(See section: ‘Guidelines for Use of Nutrition and Health Claims CAC/GL 23-1997′)

Examples

Global: NOURISHING: Nutrition label standards and regulations on the use of claims and implied claims on food. (see sub-sections on “rules on nutrient claims”)

Front-of-package labeling regulations

More recently, some governments have required that manufacturers place interpretive labels on the front of food packages to help consumers choose healthier products or avoid unhealthy products. A variety of front-of-package labeling (FOPL) systems are in use, with some indicating how healthy a food is based on its nutrient profile (e.g., star- or score-based systems) and others showing whether a product contains high amounts of sodium or other nutrients of concern (e.g., warning labels, traffic lights). To date, the only approach to show impact on improved consumer purchasing after policy implementation is a prominent warning label that highlights that a product is high in sodium, saturated fat, and/or sugar (some countries also include trans fat and/or calories). An evaluation of this model in Chile showed a 37% drop in sales for regulated junk foods with “high in sodium” warning labels, along with further reductions for foods high in sugar, saturated fat, and calories.

Implementation tools

Other resources

Examples

Chile:

- Pan American Health Organization. Approval of a New Food Act in Chile Process Summary. 2017.

- Reyes M, et al. Development of the Chilean front-of-package food warning label. BMC public health. 2019 Dec;19(1):1-1.

- Taillie LS, Bercholz M, Popkin B, Rebolledo N, Reyes M, Corvalán C. Decreases in purchases of energy, sodium, sugar, and saturated fat 3 years after implementation of the Chilean food labeling and marketing law: An interrupted time series analysis. PLoS Med. 2024;21(9):e1004463. Published 2024 Sep 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1004463

- Reyes M, et al. Changes in the amount of nutrient of packaged foods and beverages after the initial implementation of the Chilean Law of Food Labelling and Advertising: A nonexperimental prospective study. PLoS medicine. 2020 Jul 28;17(7):e1003220.

- Taillie LS, et al. Changes in food purchases after the Chilean policies on food labelling, marketing, and sales in schools: a before and after study. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2021 Aug 1;5(8):e526-33.

Government-led sodium targets for packaged food*^

Setting targets for salt levels in packaged foods is a WHO “Best Buy” intervention for addressing non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Sodium targets work best when they are government-led and accompanied by robust monitoring and accountability systems. Salt targets can be voluntary or mandatory. The initial phase of United Kingdom’s government-led voluntary targets resulted in a 15% reduction in salt intake and successfully reduced salt in many categories (He 2014); however, many other voluntary programs have been less successful, given that industry has less incentive to reformulate under voluntary programs. Mandatory targets may have a greater impact on the sodium levels in foods than voluntary approaches (Cobiac 2010).

Targets can be set for maximum levels of sodium content by food category and/or for the average levels of sodium by food category. If sales information is available, which is rare, the sales-weighted average can be used to set targets by food category (Institute of Medicine 2010). Maximum levels are easier to develop and monitor and lend themselves better to a regulatory approach; however, because they affect only the foods highest in sodium, they often have less impact on overall sodium consumed and need to be lowered over time.

Ideally, targets cover a majority of packaged foods in a country (e.g., the UK set targets for 84 food groups in 2020). If this is not possible, and certain categories can be identified as the prime sources of sodium intake, targets can be set for a smaller set of categories to start with (e.g., bread, condiments). The targets and timelines for sodium content of food categories are usually revised at defined intervals and reset to lower levels over time while also adding any new food categories that are significant contributors to sodium intake.

Implementation tools

WHO South-East Asia Region Sodium Benchmarks for Packaged Foods. 2024.

Other resources

Examples

Argentina: Government of Argentina. Law 26905. Sodium consumption – maximum values. 2013.

United Kingdom: United Kingdom salt reduction targets for 2024.

Canada: Canada’s Guidance for the Food Industry on Reducing Sodium in Processed Foods

Global: NOURISHING Framework. Section I: Improve nutritional quality of the whole food supply.

Restrictions on marketing to children^

Unhealthy food and beverages are often marketed to children. Food marketing can impact a child’s food and drink preferences, eating behavior, and food intake. WHO recommends restricting or prohibiting the marketing of unhealthy foods to children. Marketing restrictions should be robust, clear and evidence-based. The ideal marketing regulation 1) is mandatory; 2) protects children under the age of 18; 3) includes all forms of marketing (e.g., social media, in-store, television, radio, internet games, promotions in schools, sponsorship of children’s events, etc.); and 4) uses a nutrient profile model to decide which products cannot be marketed. To be effective, marketing restrictions cannot only affect programs and activities narrowly targeted at children but should also include marketing for a broader audience often seen by those under 18. Ideally, as in Chile, this should align with packaged food warning labels, food procurement standards for schools and other government institutions.

Marketing restrictions may be imposed more broadly to promote healthy eating for everyone. For example, in 2018, London, England restricted advertising for foods and non-alcoholic drinks high in fat, salt and/or sugar on all public transportation, including railways, buses and taxis (Mayor of London 2018).

Implementation tools

Other resources

World Health Organization. Protecting children from the harmful impact of food marketing: policy brief. 2022

See the resources in Section 9 for a list of WHO Nutrient Profile Models developed for the restriction of food and non-alcoholic beverage marketing to children.

Examples

Global: NOURISHING Framework: Restrict food advertising and other forms of commercial promotion.

Chile: Pan American Health Organization. Approval of a New Food Act in Chile Process Summary. 2017.

Fiscal policies

Taxation is a well-established public health approach to reducing consumption of tobacco and alcohol. Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages have been gaining momentum and have been shown to reduce consumption of sugar when the taxes are substantial; the evidence for other types of food taxes is still being established. A small number of countries, including Mexico, Hungary, Fiji, Tonga, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, have instituted junk food taxes or taxes on products that are high in sodium, sugar or saturated fat. These types of taxes may be effective in reducing both the sodium content in food products as well as the amount of high- sodium foods purchased and consumed by the public.

Taxes should be high enough to deter consumption and structured so that substitute products are healthier than taxed products. Taxes to reduce salt intake could either target high-salt foods specifically or junk foods more broadly. Combining taxes with subsidies for healthy foods (e.g., fresh fruits and vegetables) may help offset any burden that taxation may impose on lower-income people who do not change their purchasing patterns (and also increases purchasing of healthy foods).

In addition to taxation, other fiscal policies include:

- Reducing costs of healthy foods by subsidizing fruits and vegetables or other healthy foods, which can also impact purchasing behaviors and potentially reduce dietary sodium

- Tariffs on the import of unhealthy foods

Implementation tools

WHO EURO. Using price policies to promote healthier diets. 2015.

World Cancer Research Fund International.Lessons on implementing a robust sugar sweetened beverage tax. 2018. (Focuses on sugar sweetened beverage taxes, although many lessons can be applied to potential salt or junk food/HFSS taxes)

Popkin, B. and Shu Wen Ng. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: Lessons to date and the future of taxation. Plos Medicine. 2021;18.1: e1003412.

Other resources

Examples

Innovative/other policies for packaged foods

Innovative or incompletely tested interventions are listed where evidence is still emerging or research on impact has been mixed.

Food based dietary guidelines

Brazil and some other countries are moving towards guidelines that promote fresh or minimally processed foods and discourage consumption of highly processed foods. While these are not specifically targeted at changing packaged foods, they aim to disrupt the global trend toward increasing reliance on packaged foods.

Placement, price and marketing of healthy and unhealthy foods in grocery stores

The “4 Ps” of marketing (product, placement, price, and promotion) are used by food retailers to market foods to consumers and can be used to create an enabling environment for healthier choices. Researchers have found that price discounts, product promotions (e.g., food tastings), and visible/accessible placement are the most effective strategies for increasing sales of healthy foods (Hartmann-Boyce 2018, Moore 2014). While this has been studied extensively, there have been no large-scale public health interventions of this kind to date.

Location of food retailers relative to schools

Some jurisdictions have regulated what kinds of foods can be sold in establishments that are near schools. For example, the India School Children Regulation and the South Korea ‘Green Food Zones’ specify what foods are prohibited for sale and marketing within a designated perimeter of school grounds.

Prohibiting sales of unhealthy food to children

In addition to restricting marketing of unhealthy foods to children, multiple jurisdictions in Mexico have recently developed regulations that restrict the sale of unhealthy food to children unless they are accompanied by a parent. The feasibility and impact on reducing dietary sodium has not yet been assessed.

Other resources

Examples

London, UK: Evening Standard. UK’s first supermarket designed by public health experts launches in Central London

Oaxaca, Mexico: BBC. Mexico obesity: Oaxaca bans sale of junk food to children. 2020.

Interventions for Food prepared outside the home

Sodium intake from food prepared outside the home—such as from canteens, restaurants and street vendors—is increasing in many countries, as people have less time to prepare food at home and more income to spend on prepared food. Reducing sodium in these environments can be challenging, as the industry is often made up of large numbers of lightly regulated (or unregulated) small businesses; however, a number of innovative strategies have been proposed. Additionally, governments can introduce standards for foods the government purchases, serves or sells, impacting large numbers of people and setting an example for the private sector. In some cases, cities or states may have jurisdiction in these environments.

Healthy public food procurement and service policies*^

In many settings, significant amounts of food are purchased with public funds and are served and sold in public institutions (e.g., schools/school meal programs, parks, hospitals, correctional facilities, government office canteens/cafeterias). Establishing and implementing a comprehensive healthy food procurement and service policy for all government agencies increases public access to healthier meals and snacks, with more fresh and less ultra-processed food. A food procurement and service policy sets standards for healthier eating environments, provides internal consistency with a dietary sodium reduction program, and may also prompt the food industry to develop lower sodium products in order to compete for government contracts.

Public food procurement and service policies can be combined with other policies to reduce sodium, such as front-of-package labeling (Section 3.2c) and marketing restrictions (Section 3.4) to create a more effective and comprehensive package of interventions. It can also incorporate other strategies such as the use of low-sodium salt (Section 5.2) and public educational approaches (Section 5.1) to complement implementation of the policy. Further, these policies can be used as a model which can be adopted by private entities to serve or sell healthier, lower-sodium food.

Implementation tools

Other resources

Resolve to Save Lives. Resources for Healthy Public Food Procurement and Service Policies.

U.S. CDC. Healthy Food Environments. 2021.

Examples

Global: NOURISHING Framework. Section I: Improve nutritional quality of the whole food supply.

Global: Resolve to Save Lives. Resources for Healthy Public Food Procurement and Service Policies. (use filtering feature for “policy examples”)

ACT, Australia: ACT, Australia: ACT Public Sector Healthy Food and Drink Choices Policy. 2016.

New York City, USA: NYC Health. New York City Food Standards. 2008.

Quezon City, Philippines: Health Public Food Procurement in Quezon City, Philippines, 2020.

Restaurant and street food interventions

Evidence on restaurant or street food interventions is still emerging; few have been evaluated and where they have, the results have been mixed. Some of the strategies outlined below could apply to all restaurants or street vendors (Section 4.21a), while others are limited to chain restaurants (Section 4.2b). Alone, many of the strategies below may have minimal impact; however, that impact could be greatly increased if implemented together with low-sodium salt substitution (Section 5.2). Additionally, consumer-facing education approaches can encourage ordering of low-sodium dishes.

Key interventions for all types of restaurants

Leverage existing packaged food salt reduction strategies to reduce salt in foods purchased by restaurants

Ensuring that salt reduction targets for packaged foods (whether voluntary or mandatory) apply to ingredients purchased by restaurants and street vendors will likely reduce sodium levels in restaurant foods. Additionally, regulations for restaurants could leverage labeling schemes such as front-of-pack warning labels and restaurants could be required to avoid purchasing products with warning labels. While this strategy is untried, it is based on successes setting sodium thresholds for purchased foods in public food procurement policies and also trans fat thresholds for restaurant purchases of packaged foods as part of trans fat restriction policies (Angell 2009).

Other resources

Require that salt shakers and condiments high in sodium be available by request only

Several countries have restricted restaurants from placing salt shakers and high-salt condiments on tables, usually in combination with an education campaign. Customers must request the salt shaker and condiments. Similarly, if restaurants use individual salt packages, these can also be provided only upon request and the size of the package can be reduced (e.g., from 1 g to 0.5 g salt per package) to help encourage reduced consumption.

Examples

Uruguay: NPR. The Salt. Assault on Salt: Uruguay Bans Shakers in Restaurants and Schools. 2015.

Argentina: Argentina Food Law 26.905. Sodium consumption. Maximum Values. Article 5G. 2013.

Require restaurants to make a certain number of menu items with no or low added salt

To enhance customer choice within the restaurant setting, a few jurisdictions require that a certain number (or percentage) of menu items are low-salt or no salt added. Highlighting these items, often in combination with a mass media campaign about the health impact of sodium intake, can provide consumers with important information, particularly outside the chain restaurant environment, where nutrition information is limited. This intervention is likely to mostly benefit customers already motivated to reduce salt intake.

Examples

Montevideo, Uruguay: Devex. Cities and NCDs: Montevideo’s menu for reducing sodium intake. 2018.

Require a sodium warning statement on menus

Cities and countries can put mandatory policies in place requiring a health message about sodium intake and its relationship to health outcomes on menus and/or menu boards. These warning statements are sometimes only required in chain restaurants, where there is also access to nutrition information, and can be used in combination with high-sodium warning icons on specific menu items.

Examples

New York City, USA: Anekwe AV, et al. New York City’s sodium warning regulation: from conception to enforcement. American journal of public health. 2019 Sep 1;109(9):1191-2.

Create targeted education campaigns for restaurant staff and/or chefs

Many restaurant strategies include an educational component for restaurant staff, which can be delivered during mandatory food safety training required to receive a food handler license or specific training opportunities for restaurant chefs. Trainings may include information on the harms of excessive sodium intake, tips on developing new menu items with reduced sodium content, and ways to work with suppliers to source lower-sodium ingredients. Toolkits distributed to restaurants (e.g., Ma 2018) may include recipes, kitchen utensils and a standard measuring spoon.

While this education and training can complement other interventions and target particularly vulnerable communities, it is resource-intensive and may be hard to scale. Other interventions should be used in tandem to ensure the continuity of the sodium-reduction strategy.

Examples

Other resources

Interventions for chain restaurants

Require public disclosure of nutrition information at every point of sale

As a first step, all chain restaurants should be required to publicly disclose nutrition information through a nutrition board/cards for all standard menu items, along with toppings, side dishes, beverages, and promotional items. Information should include all key nutrient information that is often available on packaged food nutrition labels: calories/energy, saturated fat, total fat, trans fat, sodium, sugar, and fiber content, along with ingredients and allergen information.

Public disclosure of nutrition information allows for tracking nutrient content of menu items in chain restaurants, provides consumers information on nutrition and ingredients, and ensures that public health policies can be monitored and enforced. There is a clear need for transparency in chain restaurant nutrition information to enhance industry accountability and government monitoring of nutrition commitments. Public disclosure of nutrition information should include making it available at the point of purchase where consumers are making decisions—in stores and as part of online ordering for pickup or delivery.

Require high-sodium warning icons

Public disclosure of nutrition information requires motivated consumers to check sodium content and understand recommended daily intake limits. At least six policies are in place globally (mostly in North America, Europe, and Hong Kong) that use icons on menus to communicate sodium information to customers, reducing the burden on consumers, and some countries, including the United States and India (to be enforced from January 1, 2022), require calorie labeling on chain menu items. To date, the impact of menu labeling on menu reformulation has been mixed (Alexander 2021), with some studies showing a reduction in the sodium content of menu items and others showing no impact.

Other resources

Examples

New York City, USA: Amaka VA. et al. 2019: New York City’s Sodium Warning Regulation: From Conception to Enforcement American Journal of Public Health. 2019 Sep 1;109(9):1191-2.

Sweden: Swedish Food Agency. The Keyhole.

Hong Kong: Hong Kong Department of Health. EatSmart Restaurant Star+ Campaign.

Set sodium content limits for menu items

Governments can set thresholds for the total amount of sodium contained in a restaurant menu item. While possible in all types of restaurants, these policies are most feasible for chain restaurants, where ingredient composition is standardized and nutrition information is available. The variation in sodium content that currently exists between restaurant chains in different countries indicates that technical feasibility is not the limiting factor, and substantial reductions could be made that would improve population health (Dunford 2012).To be successful, sodium content limits would likely need to be mandatory.

Examples

England: Public Health England. Salt reduction targets for 2024. 2020. (See the description on page 4 on the requirements for the out of home food sector to meet certain sodium targets)

Set sodium (and other nutrient) content limits for meals marketed to children

Sodium limits can also be set specifically for meals targeted to children. Standards should reflect the appropriate sodium intake for children and may be combined with other nutrient requirements, such as calorie and/or fat limits and minimum servings of fruits and vegetables. A U.S. study found that the majority of meals ordered for children were not from kids’ menus, so any comprehensive policy designed to address children’s health should also encompass limits for all restaurant menu items (Hobin 2014).

In 2011, the U.S. city of San Francisco put in place nutrient thresholds for chain restaurant meals marketed to children, including a limit of 640 mg of sodium per menu item (Otten 2014). While the restaurants did not change their menus directly in response to the policy, one chain restaurant did make side dishes and beverages more healthful, affecting the overall nutritional profile of orders.

Examples

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK and the USA: Hobin E, et al. Nutritional quality of food items on fast-food ‘kids’ menus’: comparisons across countries and companies. Public Health Nutr. 2014 Oct;17(10):2263-9.

San Francisco, USA: Otten JJ, et al. Impact of San Francisco’s toy ordinance on restaurants and children’s food purchases, 2011-2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E122.

Innovative/other policies for restaurants and street food

While there are many models for potentially reducing the sodium content of restaurant meals and increasing the number of lower-sodium menu choices for consumers, the following three approaches are innovative and promising, but have not yet been widely used or evaluated.

Marketing and pricing strategies

Possible marketing and pricing strategies include proportionate pricing (i.e., eliminating price discounts for large size products); pricing promotions for healthier menu items; and making fruit, salads, water, and other low-sodium items the default choice. Interventions that include how food is displayed and where it is situated on a menu or in a buffet can also affect consumer choices.

Food ordering websites and applications

Food ordering websites and applications can be used to promote lower sodium foods. For example, they can introduce prompts, warnings or suggestions to customers while they are placing an order to encourage healthier, lower sodium choices; they can suggest restaurants that offer low-sodium options; and they can rate restaurants according to the healthfulness of food options available.

Examples

India: Swiggy Health Hub

Food safety infrastructure

For developing innovative approaches for the street vending environment, the use of food safety infrastructure may be particularly important. A street vendor model has been developed to optimize food safety and nutrition in South Africa, taking into account business viability. Surveys from food vendors in South Africa indicated high consumer willingness to purchase healthier items from street vendors and interest from vendors in organizing wholesale purchasing of healthier foods, both of which might support interventions to reduce sodium consumption (Hill 2019).

Examples

Singapore: Singapore Health Promotion Board. Healthier Dining Programme.

Thailand: Thailand Sodium Lesstaurant program

New York City, USA: Angell SY, et al. Cholesterol control beyond the clinic: New York City’s trans fat restriction. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jul 21;151(2):129-34. (example of restricting artificial trans fat in restaurants, which may also be relevant to sodium)

Interventions for sodium added in the home

There are few effective programs to reduce dietary sodium in populations where the major source is sodium added at home. Most interventions to date have relied primarily on education; however, educational programs are often resource intensive and, on their own, unlikely to meaningfully reduce population sodium intake, especially after the conclusion of the program. Using a multicomponent approach may be necessary to meaningfully address sodium added in the home. The interventions listed in this section focus on scalable solutions that potentially have a larger reach.

Behavior change interventions

While also applicable to foods prepared outside the home or packaged foods, behavior change interventions are particularly important for salt added in the home; this is where people have the most control over their salt intake.

Successful interventions typically take a comprehensive approach. For example, in Vietnam (Do 2016), the Communication for Behavior Impact (COMBI) framework (Michie 2011) was implemented, which included mass media communication, interventions in primary schools, community communication programs, and targeted communications for high-risk groups, including people with hypertension. Post-intervention, follow up surveys found significant reductions in mean salt excretion (–1.99 g/day based on 24-hour urine samples) as well as significant improvements in knowledge and behavioral outcomes.

Other resources

Examples

Media campaigns *^