Survival in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) in Sub-Saharan African countries has substantially improved in the past decade, largely due to rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART). As PLHIV age, they are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than HIV-negative adults—they are more likely to have risk factors such as high blood pressure (also known as hypertension), and other factors related to their HIV status can further increase their risk (such as side-effects of some ART medications and HIV-related chronic inflammation).1–7

In Uganda, there are approximately 1.4 million PLHIV (5.8% of all adults);8,9 78% have now achieved suppressed viral loads, meaning their HIV is under control.8 With this improved HIV control, the burden of high blood pressure is rising among PLHIV in Uganda: About one in five PLHIV there has hypertension (estimates range from 17.52%–22.8%,10 with smaller studies estimating ranges from 11– 29%).11–14 Together, these facts suggest that even as Uganda PLHIV are surviving longer with HIV, they are at risk of dying young from a heart attack or stroke caused by uncontrolled hypertension.

Even as Ugandan PLHIV are surviving longer with HIV, they are at risk of dying from a heart attack or stroke caused by uncontrolled hypertension

Using a Differentiated Service Delivery (DSD) approach to integrate hypertension and HIV care in the communities where people live

In 2019, Resolve to Save Lives (RTSL) awarded a grant to Makerere University Joint AIDS Program (MJAP)—a private, not-for-profit initiative that works to strengthen health systems for HIV/AIDS, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and other diseases—to support a two-year project integrating hypertension and HIV care at Mulago ISS, the largest HIV clinic in Uganda.

More than 16,500 PLHIV receive ART at Mulago ISS, most through “differentiated service delivery” (DSD): a flexible, patient-centered approach that makes accessing and adhering to care less burdensome. DSD has been critical to the widespread use of ART and can be used for any chronic condition, including hypertension.

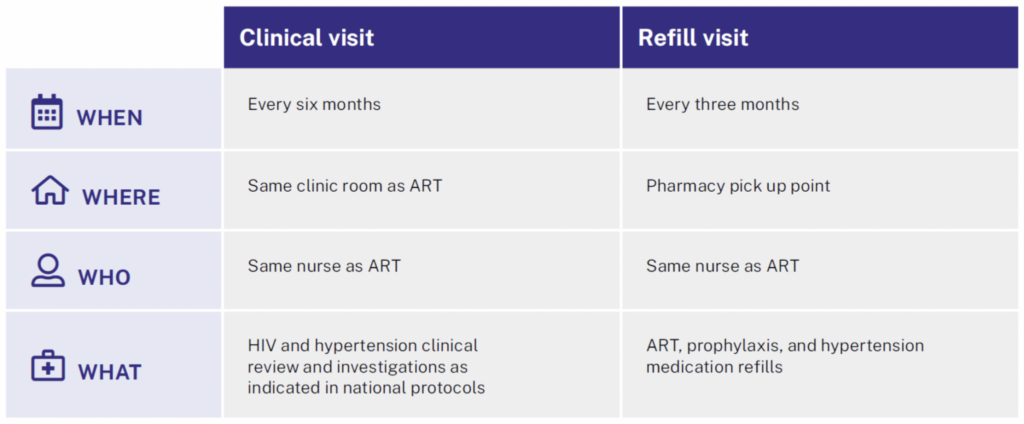

A key part of DSD involves separating clinical visits (which take place at health facilities and generally require a physician) from medication refill visits (which can be done in the community, without a physician) for patients whose HIV is under control.15 That means instead of having to travel to the clinic every month just for a routine follow-up and prescription refill, stable patients on DSD might get 3 months’ worth of medication from a source closer to home (thanks to multi-month dispensing) and only need to visit the clinic every 6 months for a full medical follow-up. This shortens time spent traveling to and attending the health facility for patients, reduces crowding at the clinic and allows physicians to focus their attention on more complicated cases requiring individualized treatment.Because this same approach can be applied to patients with controlled hypertension—and because treatment schedules for these two conditions are well aligned—hypertension care can be seamlessly added to existing DSD programs for ART.

With technical support from RTSL, the MJAP project team implemented an intervention based on the DSD approach and the WHO HEARTS technical package for hypertension control. The intervention involved five simple steps:

- Developing a standard hypertension treatment protocol: The project team worked with RTSL, the Uganda Heart Institute and the Uganda Initiative for Integrated Management of Non-Communicable Diseases to develop a simplified, stepwise, evidence-based hypertension treatment protocol to standardize hypertension treatment plans.

- Training health care workers: Clinic staff were trained on hypertension and HIV care integration as part of weekly continuous medical education (CME) sessions and mentorships .

- Team-based care and task shifting: HIV peer educators were trained to measure blood pressure for all patients during each clinic visit, and clinical officers and nurses were trained to prescribe hypertension medicines for stable patients and those requiring treatment intensification. This allowed doctors to spend more time treating complex cases.

- Ensuring access to hypertension medicines: High-quality, low-cost hypertension medicines were procured through a medicines access program initiated by Uganda’s Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Novartis Access Program. Key to the project’s success—particularly throughout the COVID-19 pandemic—was adopting multi-month dispensing to provide three-month hypertension medication refills for patients who had their hypertension under control. This served to reduce clinic visits, patient travel costs and clinic crowding.17,18

- Inclusion of hypertension specific monitoring and evaluation tools: The project team adapted the HEARTS hypertension register and CVD patient cards and distributed them to clinic providers. The CVD card was used to collate the patient’s hypertension and other CVD records. Each patient’s data was entered into both the CVD cards and the HEARTS hypertension register during each clinic visit.

The integrated care model at Mulago ISS

As part of the hypertension-HIV care integration project at Mulago ISS, the MJAP project team screened all HIV patients for hypertension. Prior to the RTSL supported pilot, while more than 95% of the clinic’s HIV patients were virally suppressed, of the 24.4% of patients diagnosed with hypertension, only 1% were initiated on treatment. Of those initiated on treatment, only 5.1% had achieved blood pressure control.

Once patients were established on ART and hypertension treatment (that is, with both conditions under control), they could choose to enroll in the integrated hypertension-HIV DSD program. Under this care arrangement, patients have a clinical visit every 6 months (during which they receive both HIV and hypertension care) and are provided with 3-month refills for both ART and hypertension medications. In between clinical visits, patients collect their medication refill directly from a pharmacy pick-up point.

Key to the project’s success—particularly throughout the COVID-19 pandemic—was adopting multi-month dispensing

Outcomes: one clinic, two deadly conditions under control

At the conclusion of the initial two-year project period, patients receiving integrated care saw a substantial improvement in blood pressure control, from 5.1% at baseline to 73% at 24 months, while HIV control remained stable at 98%.

Overall, 96% of patients initiated on integrated hypertension-HIV treatment were retained in care while receiving integrated MMD for both hypertension and HIV medications under the DSD model.

“Retention of patients in integrated hypertension-HIV care and viral suppression were above the recommended 95% UNAIDS target,” said Dr. Martin Muddu, Principal Investigator for the MJAP project team. “This means that integrating the management of hypertension into HIV care does not interrupt HIV care.”

MJAP has sustained the project beyond the end of the grant period, and will continue to look for ways to offer hypertension medicine to clinic patients at no cost. “We are committed to continue participating in initiatives towards scaling up integrated management of hypertension and HIV in Uganda and beyond,” said Dr. Muddu.

With support from MJAP, Uganda’s MoH NCD department and stakeholders have adopted a national hypertension treatment protocol, which has already been integrated in HIV guidelines. Results from the project have also led Uganda’s MoH to form a technical working group, with support from MJAP, to steer efforts for national scale up of hypertension and HIV care integration. To this effect, the Essential medicines list for Uganda and Uganda Clinical Guidelines have been revised to include more effective medications and strategies that were used in the MJAP-led project. PEPFAR-Uganda, together with the MoH, are considering integrating hypertension care into all of Uganda’s HIV clinics as part of the Country’s Operating Plan.

The Uganda MoH has also finalized the development of an NCD integration guideline and other tools to support the implementation of integrative HIV and NCD care (including hypertension, diabetes, and mental health care) for PLHIV; an initial pilot of NCD service integration by the Uganda MoH has just concluded across 124 facilities, with plans for a national scale-up.

Overall, 96% of patients initiated on integrated hypertension-HIV treatment were retained in care

Using DSD models to adapt to challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic

From March 25 to June 30, 2020, the Government of Uganda instituted a nationwide lockdown in response to COVID-19. Although health facilities remained open, use of motor vehicles was largely banned, making access difficult for many patients. Though Mulago ISS patients could access ART at other HIV clinics, most of those clinics did not stock hypertension medicines. As a result, there was a decline in hypertension control (despite sustained HIV control) midway through the project. To mitigate COVID-19 related disruption as much as possible, the team at Mulago ISS used DSD principles to provide:

- Extended drug refills (three or four months) to stable patients;

- Pre-appointment call reminders;

- Phone call follow-up with patients who missed their appointments;

- Medication delivery for patients close to the health facility during the national lockdown; and

- Links to other health care facilities for patients far from the clinic.

Lessons learned

- Hypertension treatment can be successfully integrated with HIV services to improve hypertension control rates while maintaining excellent HIV treatment outcomes.

- Patient-centered care in the DSD model (including multi-month refills, and a reduced schedule of clinical visits for those with HIV and hypertension under control) reduces barriers for patients and health care worker workload.

- Looking for synergies in care delivery can save more lives and reduce costs associated with care, both for health systems and patients.

More resources on DSD and hypertension-HIV care integration.

References

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaborative. Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996-2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(10):1387–96.

- Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384(9939):241–8.

- Muronya W, Sanga E, Talama G, Kumwenda JJ, van Oosterhout JJ. Cardiovascular risk factors in adult Malawians on long-term antiretroviral therapy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105(11):644–9.

- Malaza A, Mossong J, Barnighausen T, Newell ML. Hypertension and obesity in adults living in a high HIV prevalence rural area in South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47761.

- Shah ASV, Stelzle D, Lee KK, Beck EJ, Alam S, Clifford S, et al. Global Burden of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in People Living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation. 2018.

- Smit M, Olney J, Ford NP, Vitoria M, Gregson S, Vassall A, et al. The growing burden of noncommunicable disease among persons living with HIV in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2018;32(6):773–82.

- Althoff KN, Smit M, Reiss P, Justice AC. HIV and ageing

- Uganda country factsheet 2021. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Accessed February 17, 2023. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda.

- Summary Sheet. Uganda Population HIV-based Impact Assessment 2020 – 2021. Accessed February 10, 2023. Available at https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/UPHIA-Summary-Sheet-2020.pdf.

- Bigna JJ, Ndoadoumgue AL, Nansseu JR, Tochie JN, Nyaga UF, Nkeck JR, et.al (2020). Global burden of hypertension among people living with HIV in the era of increased life expectancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2020 Sep;38(9):1659–1668.

- Warisiima D, Balzer L, Heller D, et al. Population-Based Assessment of Hypertension Epidemiology and Risk Factors among HIV-Positive and General Populations in Rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156309. Published 2016 May 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156309.

- Niwaha AJ, Wosu AC, Kayongo A, et al. Association between Blood Pressure and HIV Status in Rural Uganda: Results of Cross-Sectional Analysis. Glob Heart. 2021;16(1):12. Published 2021 Feb 10. doi:10.5334/gh.858.

- Muddu M, Ssinabulya I, Kigozi SP, et al. Hypertension care cascade at a large urban HIV clinic in Uganda: a mixed methods study using the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation for Behavior change (COM-B) model. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):121. Published 2021 Oct 20. doi:10.1186/s43058-021-00223-9.

- Lubega G, Mayanja B, Lutaakome J, Abaasa A, Thomson R, Lindan C. Prevalence and factors associated with hypertension among people living with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:216. Published 2021 Feb 25. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.216.28034.

- Tisdale RL, Cazabon D, Moran AE, Rabkin M, Bygrave H, Cohn J. Patient-Centered, Sustainable Hypertension Care: The Case for Adopting a Differentiated Service Delivery Model for Hypertension Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Global Heart. 2021;16(1):59. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gh.978.

- Muddu M, Semitala FC, Kimera I, Mbuliro M, Ssennyonjo R, Kigozi SP, et al. Improved hypertension control at six months using an adapted WHO HEARTS-based implementation strategy at a large urban HIV clinic in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):699.

- Schwartz JI, Muddu M, Kimera I, Mbuliro M, Ssennyonjo R, Ssinabulya I, et al. Impact of a COVID-19 National Lockdown on Integrated Care for Hypertension and HIV. Glob Heart. 2021;16(1):9.

- Kimera ID, Namugenyi C, Schwartz JI, Musimbaggo DJ, Ssenyonjo R, Atukunda P, et al. Integrated multi-month dispensing of antihypertensive and antiretroviral therapy to sustain hypertension and HIV control. J Hum Hypertens. 2023;37(3):213–9.