As a deadly cholera outbreak spread last year in Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, Community Health Clubs run by local volunteers on tiny budgets managed to protect thousands of people from this water-borne bacterial disease.

Zimbabwe is no stranger to cholera outbreaks, as the disease is endemic to the southern African country. They experienced their worst outbreak in 2008, when over 4,000 people died and more than 98,000 others were estimated to have been infected.

The Community Health Clubs were created in 2015 by Harare residents to manage boreholes, the main source of water for many.

On September 6, 2018, the Zimbabwean government announced yet another cholera outbreak. By the time the outbreak had tailed off in mid-December 2018, over 9,400 suspected cases of cholera had been reported and 54 people had died.

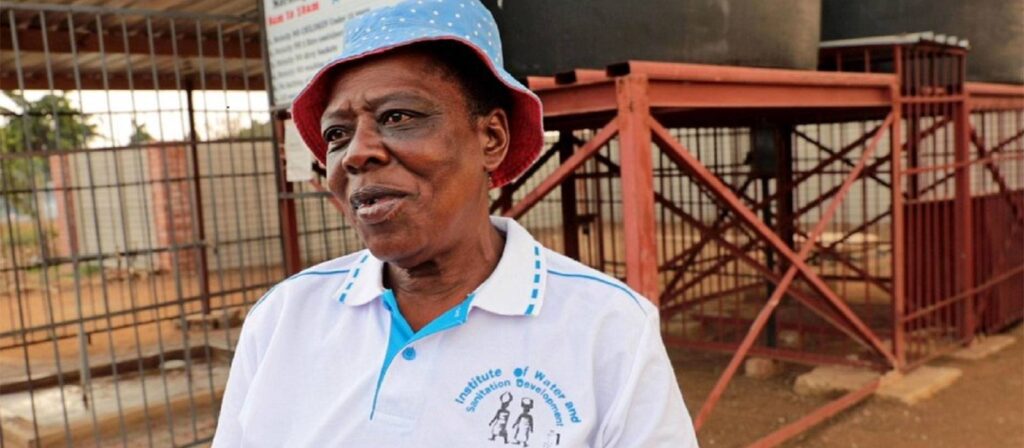

“In our area, we haven’t seen anyone with cholera, while others nearby who don’t fetch water from our water point were infected,” said Caltas Hlerima, a community-based facilitator for Kuwirirana Community Health Club in Glen View, one of the areas hardest hit by the recent cholera outbreak.

Residents pay a monthly membership fee of $1 to community health clubs in their areas to ensure that they have access to clean water. The clubs use the fees to maintain 70 boreholes in 13 residential areas in the city, with most of the money going to chlorine to purify water.

“The community health clubs provide safe, clean water to their members,” said Kuda Sigobodhla, a Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Officer for Medicins sans Frontieres (MSF) in Harare. “They collect funds which they use to buy chlorine and for security around the boreholes. Volunteers control the water points, which are open between certain hours every day. Every person who wants to get water from one of these boreholes has to pay $1 a month otherwise they can’t use the boreholes.”

During the 2018 outbreak, over 4,000 cases of cholera were reported from Harare’s Glen View, while the neighbouring Budiriro area reported almost 2,700 cases. In comparison, when MSF conducted a survey of their community health clubs with more than 8,000 members in the most affected suburbs, it found only four suspected cholera cases.

“The health clubs are a real success story. They have drastically reduced the impact of cholera in communities by sterilizing residents’ main water sources,” said Shackman Mapuranga, an emergency nurse working for MSF in Harare.

Meanwhile, Sigobodhla said that, aside from upgrading and maintaining boreholes, members of the health clubs had also been able to go out into their communities to educate people about the causes of cholera and how to sterilize water to keep them safe.

While the Zimbabwean government set up an emergency response team and trucked clean water into affected areas, the fact that the health clubs were already operational meant they had much needed help. And the establishment of the boreholes help beyond cholera outbreaks; by increasing the availability of clean water community members all benefit. Investment in public health systems provide long-lasting return on investments even after an outbreak is over.

Cover photo: Caltas Hlerima, a Community Based Facilitator and member of the Kuwirirana Community Health Club.